The Immigrant Experience, Living Well, Julian Do for The Immigrant Magazine

LOS ANGELES–For Nigerian Americans, opting for all possible medical treatments for the ailing parents is normal.

“This thinking represents the family caring and the filial duty in our culture, especially we have a long-held perception that American medicine can cure just about anything,” said Nigerian-born Dan Musa, holder of a PhD in theology, as well as an MBA. Musa owns a car import-export business in Los Angeles and is former president of the Uzuma Association USA, Inc. – California Chapter, a nonprofit organization dedicated to promoting and advancing Nigerian Americans.

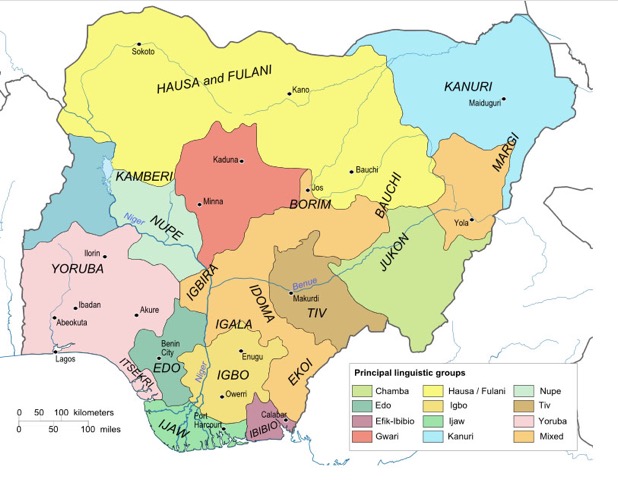

Type “Nigerian Americans,” the Internet browser would produce a surprising long list of links to this diaspora on numerous topics ranging from demographics, educational attainment, religions, regional languages and cultures, professional associations, and ethnic organizations. With more than 500 different languages and dialects spoken in Nigeria, English has become the country’s official language since gaining independence from Britain in 1960. This diversity in Nigeria reflects the heterogeneity among Nigerians in the United States.

“I am from southern Nigeria and I speak Igbo language. My wife, on the other hand, is from the north and she speaks Hausa,’ said Chike Nweke, publisher and CEO of Life and Times Magazine, an African diasporas-focus publication based in Los Angeles. He’s also a published poet and a city planning professional.

Sacred Duty–Ensuring Parents’ Health

Nweke added: “Nigeria is composed of many ethnicities and cultures, which explains why we have so many different Nigerian associations based on regionalism, religions, language, professional interests, and so on.”

Despite this great diversity, all Nigerians share one common value–that it’s the children’s sacred duty to ensure their parents’ health is well cared for and their rite of passage is with “peace and dignity.”

Solomon Gochin is a Nigerian-born psychologist, who specializes in providing supportive-living services and adaptive-living skills at Passport To Learning, Inc., in Los Angeles. Gochin came to the U.S. in the 1960s to study and decided to stay. He explains that to Nigerian elders, their “peace and dignity” derives from being cared for by family members in their final days regardless whether they are back in Nigeria or in the U.S.

He adds that at the same time, they don’t want to burden their children with difficult financial decisions.

These Nigerian cultural values are consistent with findings in the 2012 survey report titled “Final Chapter: [http://tinyurl.com/88tbseq] Californians’ Attitudes and Experiences with Death and Dying” conducted by the California Healthcare Foundation (CHCF).

“Of the survey’s 12 most important concerns at end of life for Californians, being at peace spiritually is the top priority (76%) for African Americans,” said Emma Dugas, communications officer at CHCF. “Also for this group, their second most important consideration is to not burden their families (60%).”

In general, what sets Nigerian immigrants in America apart is their exceptional educational attainment.

In early U.S. history during the 1600s and 1700s, Nigerians came to America as slaves. When slavery was abolished in 1865, this flow stopped.

Since the 1960s, political instability in Nigeria and economic opportunities in the U.S. have prompted many Nigerians, especially those among the educated elites and medical professionals, to seek political asylum, educational opportunities and a better life in America. The 2010 U.S. Census data shows that of the 264,550 Nigerian immigrants living in America, 20,358 are in California (http://tinyurl.com/lr9pm8m).

This huge brain drain illuminates why 37% of Nigerians in America hold bachelor’s degrees, 17% hold master’s degrees, and 4% hold doctorates, according to 2006 U.S. Census figures analyzed by demographer Roderick Harrison for the Houston Chronicle. That Texas city includes the largest Nigerian immigrant community in the U.S. (http://tinyurl.com/oj9qmr7). This educational achievement is higher than any other racial group in the nation.

Given this steady flow of Nigerian immigrants, who tend to maintain a strong tie with their motherland and cultures, caring for the elders’ health and observing their rites of passage are still largely observed and adhered within the Nigerian traditions.

“Since we came from a society of weak government social supports,” said the Life & Times Magazine publisher Nweke, “we therefore mainly rely on our families and kinship for every thing from birth to marriage and especially, the end of life. Family support is a necessity, a way of life.”

For that reason, sending one’s parents to a nursing home is culturally viewed as abandonment by their children, a social taboo in the Nigerian community. Furthermore, many Nigerian elders are truly frightened about being away from their family surroundings, according to Gochin, who often visits and provides counseling to Nigerian families with terminally-ill patients and aging parents.

Aggressive Treatments Risky

This filial duty also re-enforces the belief among many Nigerian Americans that all medical treatments for the ailing parents must be pursued.

But one reality that some in the Nigerian American community, especially those in the healthcare industry, have begun to recognize is the physical discomfort and potential side effects that came with some of the more aggressive and costly medical treatments.

Karl Steinberg, MD, chief medical officer of Shea Family Health [www.sheafamily.net/ ] in San Diego, believes that physical comfort should be part of the end-of-life quality care besides curative treatments.

Steinberg suggested that families who have terminally-ill members or aging parents should consider filling out a Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment (POLST) [http://capolst.org/polst-for-patients-loved-ones/] form by reviewing the treatment options with their doctors.

This planning would ensure that the selected treatments are appropriate, provide physical comfort, and would not violate any cultural taboo. Advance planning would also help avoid a financial burden to the family, the second most important concern to most African Americans. Once the one-page POLST is filled out, healthcare providers are required to honor this physician’s order, which must be signed by your doctor.

Experts also recommend that people also prepare an advance directive, [http://tinyurl.com/q97ksft] which enables them to express their wishes in greater details that the POLST form allows.

Steinberg’ advocacy is supported by the 2008 Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care study, [http://tinyurl.com/5sdp9d9] which reveals that aggressive medical interventions had worsened many patients’ quality of life, increased medical costs and even shortened their lives. This study, led by John E. Weinberg, MD, at Dartmouth Medical School, involved 4,732,448 Medicare patients at thousands of hospitals throughout the U.S.

Another study, titled “Do Unto Others,” [http://bit.ly/1iM7Sfq] by V.J. Periyakoil, MD, and her colleagues at Stanford School of Medicine, show that the majority of the nearly 1,100 doctors surveyed (88.3%) would select comfort care over aggressive treatments for themselves.

“But families shouldn’t have to make these hard decisions on their own,” said Bradley Rosen, MD, who heads the Cedar-Sinai Hospital’s Supportive Care Medicine, a palliative care program.

The Palliative Care Team

Rishi Gupta, MD, assistant director of the Cedar-Sinai program, echoed Rosen’s point by adding that with palliative care, a family would have a team of experts in medicine, social work and spirituality. Their comprehensive support would cover appropriate treatments, pain management, social work, volunteer services and bereavement follow-up for family caregivers.

“Palliative care is like a one stop-shop service for end-of-life patients,” said Vincent Nguyen, DO, director at the HOAG Cares program in Orange County, Calif. He added that palliative care provides a patient with an option to stay at home to be surrounded by family members and still get full support services. For complicated procedures, the patient can come to the hospital for treatment and often go home.

Both the 2010 New England Journal of Medicine [http://bit.ly/zVIy3m] study in the U.S. and the 2014 Canadian survey in The Lancet [http://tinyurl.com/poxwp8k] uncovered that cancer patients, who were given palliative care early, actually experienced a better quality life and even lived up to three months longer.

Camilla Zimmermann, MD, directs the Al Hertz Centre for Supportive and Palliative Care at the Princess Margaret Cancer Center in Toronto, where the Lancet study was conducted. She noted in an interview with the Science Daily, “We found that patients appreciated having a team of professionals available to provide additional support navigating the cancer system and coping with multiple medical and social issues.” (http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/02/140219075115.htm)

Chiedozio Esiobu, a nurse who came to the U.S. from Nigeria five years ago, works at a local home care agency for veterans in Los Angeles. He believes a number of Nigerian Americans, especially those in the healthcare field, have begun to reconsider the thinking of going for all possible medical treatments for the ailing parents.

“There is a growing awareness that medical treatments can only go so far, and not all are effective and yet [they are] costly,” said Esiobu.

“But our belief in family and spiritual supports will not change as these are our cultural values,” added Esiobu, who, later in the day, had planned to visit his friend’s father who is ill and bed ridden.

He said in the Nigerian culture, it’s a practice to visit friends and neighbors to pray for their ailing family members.

Julian Do wrote this article for The Immigrant Magazine with support from a New America Media fellowship, funded by the California Health Care Foundation. [http://bit.ly/1wNd22j]

Photo Credits: Odeyele Ayodeji and Family (by Titilayodeji13), Yette Lakanmi and Joanne Chavis present their aso oke head wraps hand-loomed by the Yoruba people of Southwest Nigeria, during the 2010 Multicultural Heritage Day at the Goettge Memorial Field Houston, Texas (image released by US Marine Corps) are courtesy of their authors via Wikimedia

Photos of Dr. Dan Musa and Chike Nweke are courtesy of Dan Musa and Chike Nweke.