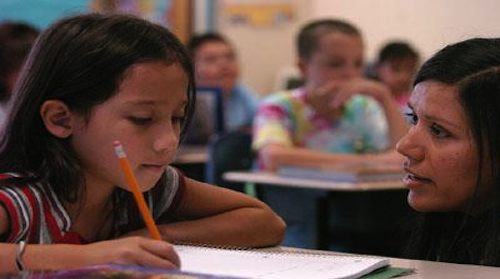

Do you understand? A question, I pondered after reading through a report released by the National Center for Education Statistics. The report, Suspension, Expulsion, and Achievement of English Learner Students in Six Oregon Districts, presents a snapshot of data gathered in 2011-2012.

The report releases disparate statistics regarding academic and behavioral outcomes of English Language Learners (ELL) students. As a professor who has conducted research on interventions for suspended youth, I have already desensitized myself to the narrative of black and brown youth in the public education system. I am familiar with black youth suspension rates tripled that of white youth suspensions. The variation of black and brown youth presence in school districts across the United States presents similar statistics for brown youth, Native American, Hispanic and Southern Asian/Pacific Islanders (please know they are more diverse than this). They share the same fate. Somehow, we continue to write a story that reflects both our lack of understanding and our lack of action.

How many of you have heard someone yell, “DO YOU UNDERSTAND?” I use caps here to exemplify the anger and frustration experienced by the speaker. As a professor, I may have yelled these words in my head when I have encountered students who refuse to read and study the material. As a mother, I have definitely yelled these words frustrated by my children’s’ inability to follow directions. More deeply, these words express my frustrations and, without minimizing the authentic voice of black and brown youth, their frustration. The perplexed and challenged public school system continues to wreak psychological violence on young people who do not readily accept the larger dominant white middle class norm. Psychological violence occurs through the isolation, verbal degradation, and treatment black and brown youth experience. These experiences in the public school system diminish their sense of identity and self-worth.

ELLs are brown youth, where roughly 86% represent individuals who enter the public school system speaking Spanish.

The changing demographics in the United States reveal there are many children living here who are immigrants and know very little English. In navigating the United States public school system, these children attempt to learn a new language, adapt to new social and cultural norms, and manage psychosocial transitions from childhood to adolescence. Public schools continue to be contentious social spaces in the United States, confounded with bullying, peer pressure, accountability standards, etc. The combination of these factors yields stress and frustration for youth.

Is the public school system punishing these students for their combined frustration?

According to the National Center for Education Statistics report, ELLs have higher rates of suspension in middle and high school than non-English learners do in Oregon schools. A majority of these suspensions were due to aggressive behavior, insubordination, and disruption. Now, let us take a brief pause and ask ourselves, “What have we historically done in this country when our identity or self-worth is in danger?”

We act out and we engage in aggressive and disruptive behavior. If this is the behavior of many adults, we can imagine what young people experience when they perceive these threats, their isolation, when implicit and explicit language counters and devalues their cultural heritage. They act out.

Is the public school system fostering a pipeline of disadvantage?

ELLs missed more days from school and had lower rates of achievement on statewide assessments in reading and math. It does not take a rocket scientist to draw the conclusion, when students are absent from school they miss important academic concepts and will be behind when they return to school. When youth are behind in school, accompanied by language barriers, they experience heightened levels of stress and anxiety. ELLs may seek to lower their sense of anxiety through disengagement, they are no longer engaged in the public school experience and begin to be absent from the learning environment. ELLs tend to have higher high school dropout rates than non-English learners.

“DO YOU UNDERSTAND” is a cry from ELLs, and more broadly black and brown youth. The United States and school districts have the power to redirect action and develop practices needed to reduce arbitrary suspensions for school violations such as excessive noise, insubordination, and disruption. Using positive behavior intervention models, integrated with culturally appropriate and bilingual education can improve academic attainment of ELLs and increase their civic engagement. By suspending these students, the United States public education system reduces opportunities among ELLs and their ability to engage in the academic pipeline. Diminishing opportunities for educational engagement will only continue to foster frustration and anger and reduce the responsibility of the public school system and increase the responsibility of another—the criminal justice system.

Dawn X. Henderson, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Psychological Sciences at Winston-Salem State University and a member of Division 27 (Society for Community Research and Action) of the American Psychological Association. Her research focuses on community and school-based alternatives for suspended youth. Any comments or feedback can be sent to dawnxhen@gmail.com.

Related article: Q&A: Cultural Fluency Key to Improving Latino Student Success