WASHINGTON, D.C. — The White House responded to years of pressure from immigrant rights groups on Wednesday, July 15, with an announcement of a new policy that will expedite the process of bringing certain family members of Filipino veterans of World War II to the United States.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — The White House responded to years of pressure from immigrant rights groups on Wednesday, July 15, with an announcement of a new policy that will expedite the process of bringing certain family members of Filipino veterans of World War II to the United States.

The policy, announced along with a number of other efforts that are a part of President Obama’s executive actions to improve the U.S. immigration system, would skip the long wait times— sometimes more than 25 years — for family members of these Filipino veterans, who are now American citizens or legal permanent residents, to immigrate legally to the U.S.

The U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) and the Department of State, according to the White House, “will work together to provide clear guidance to the public on the application process, and decisions will be made on a case-by-case basis.”

Advocates for the policy directive immediately hailed the announcement, hoping that it will be implemented soon.

Day to celebrate

“This is the day to celebrate,” said Mee Moua, executive director of Asian Americans Advancing Justice (AAJC).

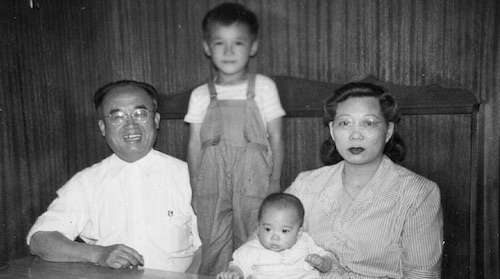

In 1941, more than 260,000 Filipinos responded to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s call to fight side-by-side with American soldiers during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. After the war, in 1945, Roosevelt promised these Filipino veterans U.S. citizenship and veterans’ benefits.

But it took nearly 50 years for the U.S. government to grant citizenship to Filipino veterans, in 1990, and since then they have been waiting for their children to join them in the U.S.

And because the U.S. government puts limits on visas so that each country can only receive 7 percent of the 226,000 family-sponsored available visas every year, the wait for Filipino American families can exceed many years or even decades.

Of the 4.2 million people waiting for family-sponsored visas, nearly one-third are from Asian countries, including the Philippines, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, China and Vietnam.

Inhumanely long backlog

“Until now, the inhumanely long visa backlog has separated them [Filipino veterans] from their children and denied them the opportunity to live together in the United States,” Moua added. “It’s long past time the U.S. made good on its promise and we hope [the] USCIS will implement this as quickly as possible.”

“We are extremely pleased to hear the good news coming from the White House, that Filipino World War II Veterans will soon be reunited with their families,” said JT Mallonga, national chair of the National Federation of Filipino American Associations.

Mallonga added, “They have endured so much pain waiting for many years for this to happen. But with this latest executive action by the Obama administration, our ailing and aging heroes will no longer be separated from their loved ones.”

Estimates indicate that there are about 6,000 Filipino veterans of World War II who are still alive in the United States today. Now in their 80s and 90s, most of them need the care and assistance of their families, and they long to reunite with their family members during their golden years.

Parole as an avenue

“Parole is an avenue provided under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA) that allows individuals to come to the United States for a temporary period of time,” according to the White House announcement, “based upon urgent humanitarian reasons or significant public benefit.”

However, the Obama administration has not provided any specific details on the eligibility requirements of the policy, or when will it be implemented. Considering it is part of Obama’s executive actions, many are concerned that the policy may no longer be enforced once his presidential term ends in 2016.

Recognizing the challenges ahead, Erin Oshiro, AAJC’s immigration and immigrant rights program director, says that advocacy groups are now reaching out to the administration and putting more pressure to move forward with the implementation of the new family reunification policy for Filipino veterans.

“It never moved quickly in D.C. Time is really of the essence here,” Oshiro added. “But this is an opportunity for us and the community to weigh in and ask the White House to make this program possible.”