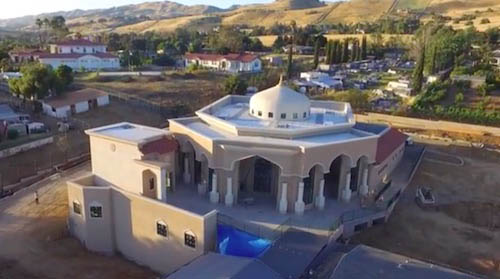

Above: the Evergreen Islamic Center in San Jose, California.

Ramadan begins May 27 this year. For Muslims around the world, the 30-day period is marked by anywhere from 14 to 16 hours of fasting, during which the throat gets parched and the stomach complains as adherents seek to strengthen their acquaintance with the Divine.

But for the more than 3 million Muslims in America, Ramadan this year will be different in one particular way: We will be thinking more deeply about the fate of our country and its direction.

During the presidential campaign, then candidate Trump made no bones about maligning Islam and Muslims. “We have a problem in this country; it’s called Muslims,” he said at a 2015 town hall in New Hampshire.

He repeatedly promised to close mosques and create a Muslim registry in America if elected. Within a week of becoming president, he signed an executive order blocking Syrian refugees and travelers from seven predominantly Muslim countries from entering the United States, orders that, for now, remain blocked by the judiciary.

Given the history of his inflammatory rhetoric, I was curious to hear what Trump would say in Saudi Arabia, the birthplace of Islam and the first stop of an overseas tour that also took the president to Israel and the Vatican.

In a speech to more than 50 Arab and Muslim nations and their leaders, Trump asked Muslims to “purge the foot soldiers of evil” from their societies. “This is not a battle between different faiths, different sects, or different civilizations,” he observed. “This is a battle between Good and Evil … We are not here to lecture. We are not here to tell other people how to live, what to do, who to be, or how to worship. Instead, we are here to offer partnership — based on shared interests and values.”

This was in the spirit of Ramadan, I thought. I nodded in agreement (because that’s what Muslims like me have been saying all along). But then I read what Trump said in a meeting with the Emir of Qatar before the speech: “One of the things we will discuss is the purchase of lots of beautiful military equipment because nobody makes it like the United States.”

During his stay, Saudi Arabia reportedly signed an agreement to buy “beautiful” American arms worth $110 billion, arms that will, according one analysis, likely go toward the civil war in Yemen, a conflict that has yielded untold suffering and allegations of potential war crimes that could ensnare the United States alongside Riyadh.

During Ramadan, Muslims are required to abstain not only from food and drink but also from such vices as anger, impatience, or arrogance. The food part is relatively easy; it is the cleansing of the heart that is harder, particularly in these troubled times.

And while there is no estimate of what percentage of Muslim adults fasts — because fasting is considered a personal pledge between a believer and God – what is undeniable is that mosque attendance goes up dramatically during Ramadan, its social aspect most evident at ‘Iftar’ (Arabic for ‘breaking the fast’) just after sunset.

At San Jose’s Evergreen Islamic Center (EIC), we invite neighbors, co-workers, local politicians, police officers and anyone curious about our faith, to our weekend Iftars. Polls show that most Americans who harbor negative opinions about Muslims have never met one. If people can break bread together, we expect hate and enmity to recede. And it indeed does, based on what we have experienced, despite the occasional hate mail and taunts of “go back home.”

Many of the employers I have encountered, moreover, are aware of the demands Ramadan makes on believers and are sensitive to the needs of their Muslim employees. By the time we complete the special nightly prayers of Ramadan called ‘Taraweeh’, for instance, it is often past midnight. That means that many of us have to do with no more than 4-5 hours of sleep per night during workdays. If you find your Muslim colleagues sleepy or slow during working hours in Ramadan, you will perhaps know why.

Indeed, I have found nothing but empathy from colleagues and co-workers. When I worked in the tech industry, my co-workers avoided eating in my presence and gave me space to offer my afternoon prayers. It’s the same in the college where I now teach, where students sometimes ask me to slow down and conserve my energy while I am trying to explain a difficult concept in, say, algebra.

Ramadan is the believer’s gateway to the ineffable and the transcendent, when Muslims make an effort to pay more attention to the little things around us (which often turn out to be the big things), smile from the heart at friends and strangers, make more charitable donations.

So I find myself focusing this year on Ramadan’s message of hope, its rejection of despair, and the generosity of the average American. What keeps me awake is knowing the “beautiful” weapons will likely not go toward combating terrorism.