Magazine, The Immigrant Experience, By Julian Do, Contributor to The Immigrant Magazine

Los Angeles — The Covid-19 pandemic has caused massive reversal of migration and rise in hunger worldwide. Their consequences in terms of economic and environmental fallout are felt globally, including in developed countries like the US.

From the international development perspective, the 2020 decade kicked off with great optimism. Coming out of the 20th century, more than 1 billion people had lifted themselves out of poverty; hunger and diseases were subsiding; and millions of low-cost laborers could be called across borders.

With rising global trades, travels, and online connectivity, wealthy nations like the US have employed millions of migrant labors — many of whom are undocumented — for huge construction projects and food production; multinational corporations like Nike and Ikea have hired millions of workers from rural areas to produce everything from shoes to furniture.

Lurching around the corner, however, was a growing concern about climate change caused by these massive industrial productions to meet the huge consumer demand. Nevertheless, the euphoria was dominant.

According to the World Migration Report 2020 by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), 2019 saw 272 million migrants — with two-thirds being laborers, traversing the globe. The US (50.7 million migrants) was the top destination country for international migrants while the top three countries with the largest number of migrants living abroad were India (17.5 million), Mexico (11.8 million), and China (10.7 million).

Economically, the IOM report also indicates that in 2018, international remittances, a significant income source for many developing nations, reached $689 billion. There’s a clear correlation between international migration and remittances as the US ($68 billion) is also the top remittance-sending nation and likewise, the leading three remittance recipients were India ($78.6 billion), China ($67.4 billion), and Mexico ($35.7 billion).

But the Covid-19 pandemic has suddenly halted all of that. Like a videotape playing backward, everything has started to recede at the beginning of February, when the world woke up to the realization that Covid-19 was a pandemic in the making. And the reactions have been unprecedented in human history.

The massive reduction of human contacts to prevent the spread of the disease has frozen almost all economic activities from trades to construction and manufacturing.

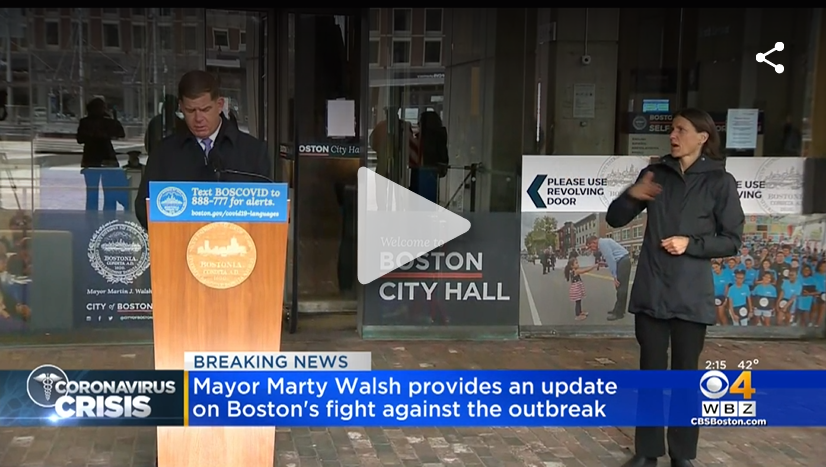

“International migration has basically ground to a halt and then reversing,” Demetrios Papademetriou, co-founder and president emeritus of the non-partisan think tank Migration Policy Institute, said at the May 8 teleconference organized the Ethnic Media Services. “All borders are closed. Only a small number of essential workers like healthcare workers are allowed to cross.”

Over the course of just three months since February, shutdown construction projects and factories have left millions of migrants and laborers no choice but to return to their mother countries and home villages.

“In Europe, the Romanian government has announced that in the last seven weeks, about 1.3 million Romanians have returned to Romania,” said Papademetriou. That’s about 7% of Romania’s total population of 19 million.

With rising unemployment across the globe, Papademetriou added that the World Bank has estimated a loss of about $100 billion in international remittances just in the first half of 2020.

At the time when global collaboration is needed most to combat the pandemic, countries abruptly have turned inward and even competed for health supply resources.

UN agencies like the World Health Organization (WHO), the World Bank, and the UN High Commission on Refugees (UNHCR), deprived of resources and political supports from rich countries, are flailing. They are unable to coordinate or marshal any sense of orders to mitigate the disease infection, alleviate the economic fall out, and assist the millions of migrants stranded at borders across the globe.

In Africa, an estimated 1.2 million migrants are displaced along “bordering areas of Burkina Faso, Niger, and Mali”, according to the The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET), a nonprofit provider of information on food insecurity.

At the Mexico-US borders, tens of thousands of Latino migrants and asylum seekers have also started heading back to their homelands in Central and South America.

These unfolding events concern Dulce Gamboa, policy specialist at the Christian nonprofit-organization Bread of the World, and Dan Nepstad, president and founder of Earth Innovation Institute, an environmental nonprofit organization.

World hunger, largely concentrated in Africa due to wars and conflicts, had signs of decline at the beginning of 2020. With the pandemic, the number people facing food crises is now projected to double, reaching 265 million people in 2020, said Gamboa.

FEWS NET reports that currently in Yemen, “17 million people are in need of food assistance,” which is more than half of the country’s population of 28 million population; and in Zimbabwe, “inflation has top over 675%”.

Gamboa’s organization believes leading nations should create a $12 billion global Covid-19 emergency relief “to ensure funding for global food and nutrition programs” and to help underdeveloped countries coping with economic crises and “access to new vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments”.

While many environmentalists think factory closures and the decline number of cars on the roads have temporarily helped decreasing pollution, the reversal of migration might more than off set any reduction.

For example, with tens of thousands of unemployed Brazilians are returning the Amazon, which generates about 40% of greenhouse gas emission, Nepstad feared that it would put a lot of

pressures on people to resort back to the ancient survival methods of slash and burn agriculture and hunting wild animals for food.

“Our world is connected. What’s happening on the grounds in the Amazon and elsewhere on earth affects us directly,” said Nepstad. As a result, the world might see more deforestation and experience less clean air in the near future especially during the upcoming burning season from July to October in the Amazon, he forecasted.

Additionally, among the returning Brazilians are those with positive Covid-19 infections. Once back in the Amazon, they might spread the disease among their villagers and it would be difficult to contain and provide treatments.

“We shouldn’t view what’s happening there as black and white, right and wrong. Instead, we should empathize with these people. They are just trying to survive and we must work with them, help them to avoid deforestation and fight the disease,” said Nepstad.

For this reason, both Nepstad and Papademetriou concurred with Gamboa about the call for a global Covid-19 relief from the rich nations. Since everyone is connected, helping others is also helping yourselves.