Magazine, The Immigrant Experience, Yahoo News, Matthew Korfhage, York Daily Record

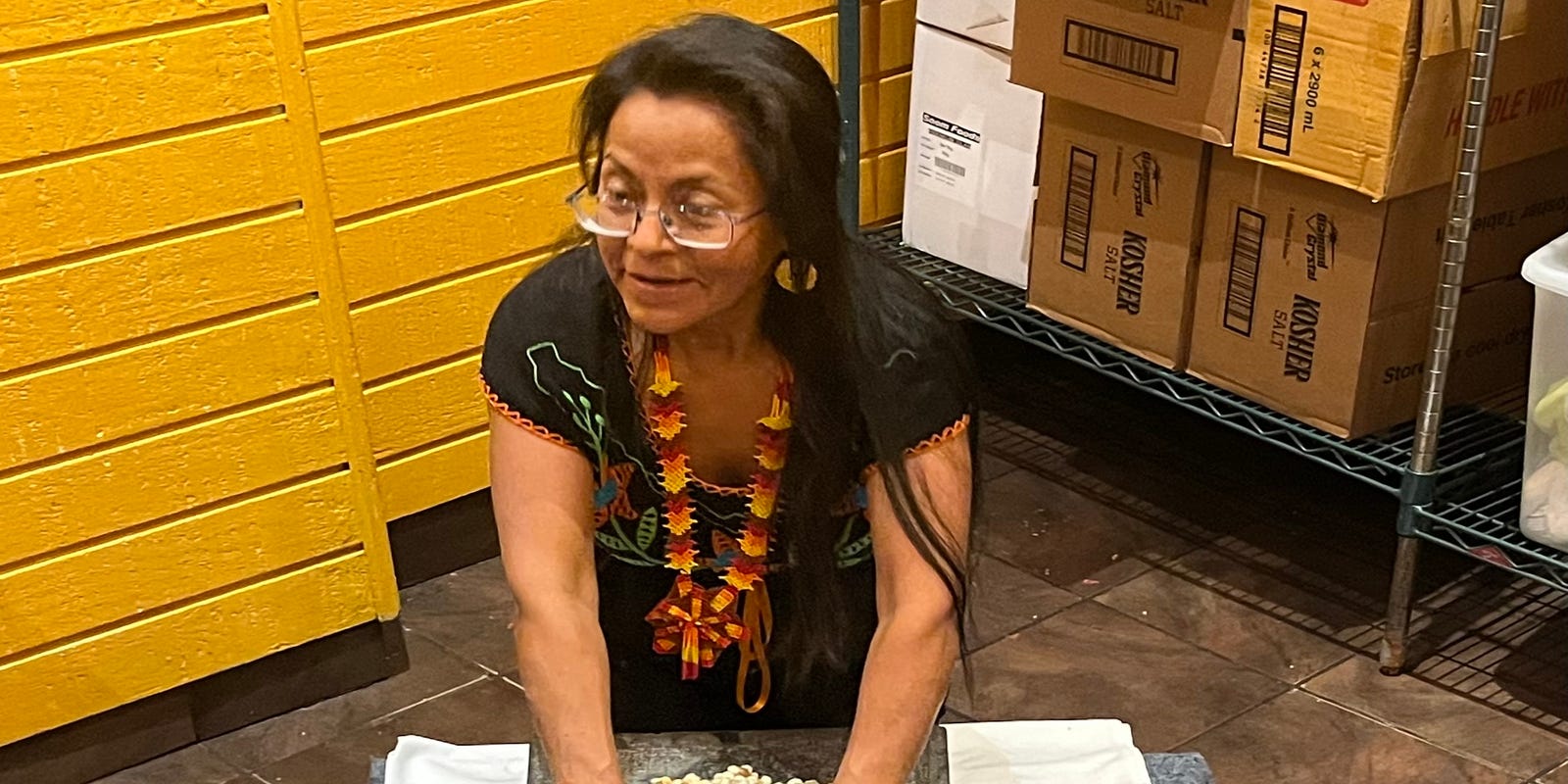

Kneeling on the tile of the People’s Kitchen in South Philadelphia, Carmen Guerrero leaned her whole body into the stone.

This is how she had learned to make corn masa for tortillas with her mother in Mexico. And it is how she learned the craft from her grandmother, pressing down the midnight-blue corn with a crackle like the crunching of leaves, working the grain over and over with a rounded stone across a porous lava table called a metate. Wetted with the palm of her hand, the corn-masa dough took on the satisfying consistency of potter’s clay.

Centuries before Columbus, this is also how it was done.

“You see? You have to use muscles!” she said, laughing as an onlooker attempted to take over the grind.

For Guerrero, the corn is more than just corn: It is a once-severed link to the past, and the means to a livelihood. The event at community restaurant People’s Kitchen on Nov. 18 was an open house for a new worker-owned collective called Masa Cooperativa, designed to give undocumented immigrants a legal way to profit from their labor.

Using rare varieties of indigenous corn thought lost for generations, the members of Masa Cooperativa make and sell corn masa to local restaurants and at special events beginning in January, which they will announce on Masa Cooperativa’s Facebook page.

The six members of the collective also help harvest the corn, from farms in nearby Berks and Lancaster counties or in the backyards of the collective’s members.

“I’m so proud, because of my roots as an Indigenous person, Aztec and Mayan,” Guerrero said. “I remember how my grandparents and my parents worked. And I remember it was very hard. But I’m very proud about doing this.”

Guerrero’s presence at the public event was in some ways an act of courage. She is herself an undocumented immigrant.

She was kidnapped in Mexico on Christmas Eve 1999. Though she was released two days later, she no longer felt safe in the place where she grew up. And so she fled north, to an unfamiliar country she had never intended to call home.

She’d owned a food distribution company in Mexico City. But in Pennsylvania, she had no legal means of finding employment. Like many in her situation, she instead worked long hours at low wages, cleaning hotel rooms or washing dishes at restaurants.

Guerrero still can’t file employment papers. But there’s a loophole of sorts. The same way Belgians own Budweiser and Australian Rupert Murdoch owns FOX News, she can legally own a business in the United States and profit from it.

“What I came to understand after talking to immigration attorneys is that to be a business owner, you don’t have to have any sort of legal immigration status,” said Ben Miller, co-owner of renowned taqueria South Philly Barbacoa and one of six founders of Masa Cooperativa. “And that’s not a law that’s going to change anytime soon. Because there are billionaire investors in other countries that open up factories in the United States. And they’re not going to be barred from making money from their business.”

Worker-owned cooperatives, often more associated with organic grocery stores and left-leaning cafes, are increasingly becoming a means for immigrants and other underserved groups to take ownership of their work and avoid exploitation of their vulnerable legal status — particularly in areas such as New York and the West Coast that have organizations in place to help cooperatives organize.

“It’s not a safe harbor for their immigration status. But as far as earning a living … we’re trying to change the narrative from immigrants taking jobs to immigrants creating jobs,” said Charlotte Tsui, an attorney for Oakland-based Sustainable Economies Law Center, which provides legal services for nonprofits and community organizations. She stresses that businesses formed by undocumented immigrants must pay taxes, same as any other business.

One of the main barriers to immigrants becoming self-employed, said Tsui, is that many don’t know the option is available to them.

“There’s an element of wanting to encourage other undocumented workers to not be afraid to create a means of livelihood for themselves,” Tsui said.

Forging an immigrant-owned tortilla cooperative

The seeds of Masa Cooperativa were planted at South Philly Barbacoa.

Cristina Martinez, chef and co-owner of the famed taqueria, is an undocumented immigrant who’d lost her job as a pastry chef after her work status was discovered. She started her own barbacoa business from her kitchen, before expanding into a full-service restaurant in 2015.

South Philly Barbacoa’s whole-animal butchery and fresh-masa tortillas, along with Martinez’s story, propelled the restaurant onto documentary series “Chef’s Table” and into the pages of Bon Appetit magazine. That success became, in part, a proof of concept for the Cooperativa.

Hard work has always been the secret to delicious tortillas. The same way a world-class sandwich begins with fresh-baked bread, a taco can only be as good as its wrapper.

From the beginning, South Philly Barbacoa was one of few places in Pennsylvania to make tortillas according to old and laborious traditions, from fresh corn that must first undergo a process called nixtamalization, cooked with an alkaline substance called lime that helps soften its kernels and release the nutrients buried within.

But the overwhelming majority of tortillas served in United States restaurants are stamped out in a factory. Even among taquerias that press their own corn tortillas, versions made with fresh masa can be difficult to find. Instead, most tortillas are made from industrial flour.

What goes missing is texture, and flavor: the telltale soft give and light chew with each bite, the encompassing aroma of grain, the surprising complexity of heirloom corn that’s been softened and gently slipped from its hulls. By comparison, a supermarket tortilla might as well be a hot dog bun.

“The tortilla that’s fresh off of the flattop is kind of incomparable to anything, you know?” Miller said.

A few years ago, South Philly Barbacoa ended up with a bumper crop of corn from local farmers — and began selling extra masa that they didn’t need for the restaurant’s own tacos and quesadillas.