This post was originally published on this site

Caribbean Immigrants in the United States

The Little Havana neighborhood of Miami. (Photo: Raul Rodriguez/iStock.com)

The Caribbean, which is known for high emigration rates, has been the source of steady migration to the United States over the past several decades. Immigrants from Caribbean island nations have a wide range of ethnic, linguistic, and educational backgrounds, with the vast majority coming from Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, or Haiti. The 5.3 million immigrants from the region in the United States in 2024 accounted for 10 percent of all 50.2 million U.S. immigrants.

Emigration trends from the Caribbean have evolved over time. Throughout the 20th century, movements from the region to the United States were largely shaped by U.S. labor demand. In the early part of the century, U.S. firms recruited Caribbean workers to help build the Panama Canal, and many later settled in New York. During World War II, many agricultural labor shortages were filled with Caribbean workers, particularly in Florida. After the war, many U.S. companies recruited English-speaking workers from the Bahamas, Barbados, and Jamaica to fill jobs in health care and agriculture. The removal of restrictive U.S. immigration quotas in 1965 that had limited most non-European immigration and the creation of a new system prioritizing family reunification and employment paved the way for more arrivals. At the same time, a revolution in Cuba and oppressive political regimes in the Dominican Republic and Haiti fueled further emigration. The 1959 Cuban Revolution alone prompted the region’s first large-scale humanitarian exodus, with an estimated 1.4 million people fleeing to the United States.

Ongoing political volatility, economic instability, and natural disasters have intensified emigration from the Caribbean in recent years. These include the deep insecurity and instability witnessed in Haiti since the 2021 assassination of President Jovenel Moïse and worsening economic conditions in Cuba accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic that prompted the largest emigration of Cubans in more than 30 years.

Compared to the overall foreign-born population in the United States, Caribbean immigrants are more likely to be naturalized U.S. citizens, to have obtained permanent residence (also known as a green card) through family sponsorship or humanitarian protection pathways, and to have arrived since 2010. They also tend to have lower incomes and are less likely to have a college degree.

This Spotlight provides information on the Caribbean immigrant population in the United States, focusing on its size, geographic distribution, and socioeconomic characteristics.

Click on the bullet points below for more information:

- Size of Immigrant Population over Time and by Country

- Distribution by State and Key Cities

- English Proficiency

- Age, Education, and Employment

- Income and Poverty

- Immigration Pathways and Naturalization

- Unauthorized Immigrant Population

- Health Coverage

- Diaspora

- Top Global Destinations

- Remittances

Size of Immigrant Population over Time and by Country

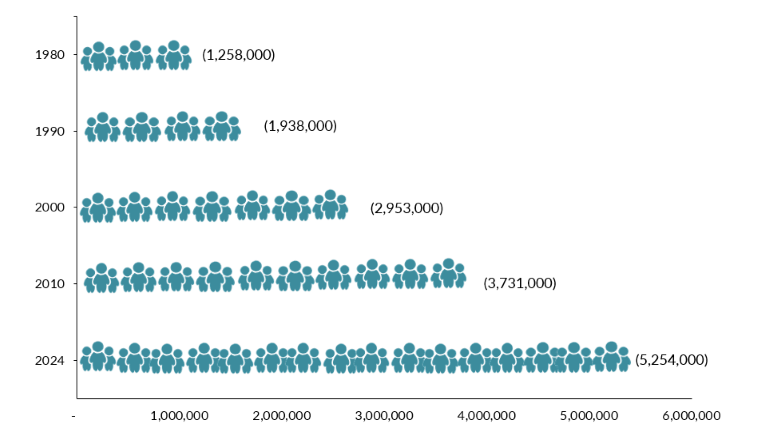

In 1980, there were about 1.3 million Caribbean immigrants in the United States. The population grew by 54 percent by 1990 and has grown quickly in subsequent decades (see Figure 1). From 2010 to 2024, the number of Caribbean immigrants grew by 41 percent, almost twice as fast as the overall U.S. foreign-born population (26 percent).

Figure 1. Caribbean Immigrant Population in the United States, 1980-2024

Sources: Data from U.S. Census Bureau’s 2010 and 2024 American Community Surveys (ACS), and Campbell J. Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000” (Working Paper no. 81, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, February 2006), available online.

Approximately 90 percent of all Caribbean immigrants in the United States in 2024 were born in one of four countries: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, or Haiti (see Table 1). Among groups with sizable populations, the fastest growing have been Cubans (an increase of 53 percent between 2010 and 2024), Dominicans (48 percent), and Haitians (46 percent).

Table 1. Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, by Country of Origin, 2024

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 ACS.

Distribution by State and Key Cities

Most Caribbean immigrants live in states along the East Coast. Florida and New York were home to 63 percent of all Caribbean immigrants as of the 2019-23 period. An additional 16 percent resided in New Jersey, Massachusetts, or Pennsylvania. The top counties for Caribbean immigrants were Miami-Dade County and Broward County, Florida, and Kings County, Bronx County, and Queens County, New York. Together, these five counties were home to 39 percent of all Caribbean immigrants in the country.

Click here for an interactive map that highlights the states and counties with the highest concentrations of immigrants from the Caribbean or other regions.

The top cities for Caribbean immigrants were the greater New York, Miami, Boston, Orlando, and Tampa metropolitan areas. About 67 percent of all Caribbean immigrants lived in one of these five cities as of 2019-23 (see Figure 2). In Miami, 20 percent of the overall population was born in the Caribbean, a far larger share than any other city.

Figure 2. Top Metropolitan Destinations for Caribbean Immigrants in the United States, 2019-23

Note: Pooled 2019-23 ACS data were used to get statistically valid estimates at the metropolitan statistical-area level for smaller-population geographies. Not shown are the populations in Alaska and Hawaii, which are small in size. For details, visit MPI’s Migration Data Hub for an interactive map showing geographic distribution of immigrants by metro area, available online.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from U.S. Census Bureau’s pooled 2019-23 ACS.

Click here for an interactive map that highlights the metro areas with the most immigrants from the Caribbean or other regions.

Caribbean immigrants’ proficiency in English tends to mirror that of the overall U.S. foreign-born population, but rates vary significantly by origin, which is unsurprising given that Spanish is the official language for some of these countries, English for others, and Haitian Creole, French, Dutch, or Papiamento for yet others. In 2024, about 46 percent of Caribbean immigrants ages 5 and over reported speaking English less than “very well,” compared to 47 percent of all immigrants. Cubans (67 percent) and Dominicans (63 percent) were more likely than other Caribbean immigrants to speak English less than “very well.”

Meanwhile, 29 percent of Caribbean immigrants reported speaking only English at home, compared to 16 percent of the total foreign-born population. The overwhelming majority of immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago (94 percent) and Jamaica (89 percent) spoke only English at home.

Age, Education, and Employment

In 2024, 72 percent of Caribbean immigrants were of working age (18 to 64 years old), lower than the share of all immigrants (76 percent) but higher than that of U.S. natives (58 percent; see Figure 3). Caribbean immigrants’ median age was 49, higher than that of immigrants overall (47) or the U.S. born (37).

Figure 3. Age Distribution of the U.S. Population, by Origin, 2024

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 as they are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 ACS.

About 21 percent of Caribbean immigrants ages 25 and older had less than a high school diploma as of 2024, versus 24 percent of all foreign-born adults and 7 percent of U.S.-born adults. One-quarter of Caribbean immigrants held a bachelor’s degree or higher, a lower rate than the other two groups (see Figure 4). Immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago and Jamaica were more likely to have a college degree (31 percent and 30 percent, respectively) than those from the Dominican Republic (19 percent) and Haiti (22 percent).

Figure 4. Educational Attainment of the U.S. Population (ages 25 and older), by Origin, 2024

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 as they are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau 2024 ACS.

Click here for data on immigrants’ educational attainment by country of origin and overall.

Nearly 11,800 students from the Caribbean were enrolled in U.S. undergraduate or graduate degree programs during the 2023-24 academic year, according to the Institute of International Education. Jamaica (3,200), the Bahamas (2,500), and the Dominican Republic (1,500) were the top countries of birth of students from the region. Caribbean students made up 14 percent of the 85,900 students from the broader Latin America and Caribbean region, and 1 percent of all 1.1 million international students in the United States.

Caribbean immigrants had a civilian labor-force participation rate of 67 percent in 2024, roughly similar to that of the overall foreign-born population (68 percent) and higher than that of the U.S. born (63 percent). Among the largest Caribbean immigrant groups, Haitians and Jamaicans (70 percent each) had some of the highest participation rates, while immigrants from Cuba (64 percent) and Trinidad and Tobago (65 percent) had some of the lowest.

About 29 percent of Caribbean immigrants were employed in management, business, science, and arts occupations, comprising the largest occupation group, followed by workers in service occupations (25 percent) and production, transportation, and material moving occupations (20 percent).

Figure 5. Employed Workers in the Civilian Labor Force (ages 16 and older), by Occupation and Origin, 2024

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 as they are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 ACS.

The average median household income for Caribbean immigrants in the United States in 2024 was $66,500, which was lower than that of both the overall immigrant population (about $82,400) and U.S.-born households ($81,400). People from Jamaica reported some of the highest median household incomes ($81,400), followed by households led by immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago ($77,900) and Haitians ($72,500). Immigrants from the Dominican Republic ($53,400) had lower median household incomes.

In 2024, 16 percent of Caribbean immigrants lived below the poverty line, compared to 14 percent of all immigrants and 12 percent of U.S.-born residents. Poverty rates were higher among immigrants from the Dominican Republic (20 percent) and Cuba (18 percent) and lower among immigrants from Jamaica (10 percent). (The U.S. Census Bureau defines poverty as having an income below $32,100 for a family of four in 2024.)

Immigration Pathways and Naturalization

As of 2024, about 60 percent of Caribbean immigrants were naturalized U.S. citizens, compared to 51 percent of immigrants overall. Immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago (75 percent) were more likely to be naturalized than those from Cuba (54 percent), Haiti (55 percent), and the Dominican Republic (57 percent).

Forty percent of Caribbean immigrants entered the United States before 2000, and approximately 42 percent arrived since 2010 (see Figure 6). Immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago (62 percent) were especially likely to have arrived before 2000. In contrast, half of Cubans and 47 percent of Haitian immigrants arrived in 2010 or later.

Figure 6. Caribbean and All Immigrants in the United States, by Period of Arrival, 2024

Note: Percentages may not add up to 100 as they are rounded to the nearest whole number.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 ACS.

One in six of the 1.2 million immigrants who became lawful permanent residents (LPRs, also known as green-card holders) in fiscal year (FY) 2023 was from the Caribbean. Family reunification was the main pathway to permanent residence for Caribbeans, used by 76 percent of all 194,000 new LPRs from the region that year, compared to 64 percent of all new green-card holders. Another 22 percent of Caribbeans became LPRs after being resettled as refugees or being granted asylum, compared to 8 percent of all new LPRs. Only 1 percent of new green-card holders from the Caribbean obtained the status through employment-based sponsorship, compared to 17 percent of all new LPRs.

Most new LPRs from St. Vincent and the Grenadines (81 percent), Grenada and the Bahamas (each 78 percent), Saint Lucia (77 percent), and Haiti (76 percent) received their green cards as immediate relatives of U.S. citizens. Cubans (52 percent) were more likely to have obtained their green cards by adjusting from refugee or asylee status.

Unauthorized Immigrant Population

The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that about 575,000 (4 percent) of all 13.7 million unauthorized immigrants in the United States as of mid-2023 were from Caribbean countries. Of these unauthorized immigrants from the Caribbean, the largest group was from the Dominican Republic (37 percent of unauthorized immigrants from the Caribbean), followed by Haitians (31 percent), Cubans (15 percent), and Jamaicans (10 percent).

Click here for MPI data of the unauthorized immigrant population in the United States as of mid-2023.

Many unauthorized immigrants have benefitted from liminal (temporary) statuses offering protection from deportation and work authorization. In recent years, many Cubans and Haitians have benefitted from these “twilight” legal statuses including Temporary Protected Status (TPS) and humanitarian parole. The Trump administration has sought to end those statuses, although its effort to cancel TPS for Haitians was temporarily blocked by a federal judge. As of March 2025, 331,000 Haitians held TPS, accounting for 25 percent of the nearly 1.3 million TPS holders in the United States at the time. More than 110,000 Cubans and 211,000 Haitians arrived and received temporary protections under the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, and Venezuelan (CHNV) humanitarian parole program created during the Biden administration; the Trump administration has terminated the program and has been permitted by the U.S. Supreme Court to begin removing some CHNV recipients.

Additionally, an estimated 4,900 Caribbean immigrants as of June 2025 were beneficiaries of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides temporary deportation relief and work authorization to unauthorized immigrants who arrived as children and meet the program’s education and other eligibility criteria. This population represented approximately 1 percent of all 515,600 active DACA recipients. DACA recipients from Jamaica (1,700), the Dominican Republic (1,300), and Trinidad and Tobago (1,100) represented the largest groups.

Click here to view the top origin countries of DACA recipients and their U.S. states of residence.

Caribbean immigrants were slightly less likely than immigrants overall to lack health insurance as of 2024 (15 percent versus 18 percent, respectively; see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Health Coverage for Caribbean Immigrants, All Immigrants, and the U.S. Born, 2024

Note: The sum of shares by type of insurance is likely to be greater than 100 because people may have more than one type of insurance.

Source: MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2024 ACS.

The Caribbean diaspora in the United States was comprised of more than 9.1 million individuals who were either born in the Caribbean or reported ancestry of a Caribbean country, according to MPI tabulation of data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2023 American Community Survey.

The Cuban diaspora was the largest, with more than 2.8 million members, followed by the 2.6 million U.S. residents who had links to the Dominican Republic and 1.4 million with ties to Jamaica. Although they are U.S. nationals at birth and therefore not foreign born, Puerto Ricans comprised the largest Caribbean diaspora in the United States, at 6.4 million as of 2023.

Click here to see estimates of the 35 largest diasporas groups in the United States in 2023.

Globally, approximately 9.6 million migrants from the Caribbean resided outside their countries of birth, according to mid-2024 estimates by the United Nations Population Division. Of these, about 10 percent lived elsewhere within the region. The United States was by far the top destination for Caribbean migrants, followed by Spain (417,000), Canada (398,000), and Chile (209,000).

Click here to view an interactive map showing where migrants from the Caribbean and other origins have settled worldwide.

Migrants and other individuals worldwide sent approximately $20 billion in remittances via formal channels to Caribbean countries in 2024, a 158 percent increase since 2010, according to World Bank estimates.

Figure 8. Annual Remittance Flows to the Caribbean, 2000-24

Note: Data for 2024 are an estimate.

Source: Dilip Ratha, Sonia Plaza, and Eung Ju Kim, “In 2024, Remittance Flows to Low- and Middle-Income Countries Are Expected to Reach $685 Billion, Larger than FDI and ODA Combined,” World Bank blog post, December 18, 2024, available online.

Some Caribbean economies are more dependent on remittances than others. Remittances sent via formal channels accounted for 19 percent of Haiti’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 18 percent of Jamaica’s GDP in 2024. Although the largest total remittances to the region went to the Dominican Republic ($11 billion), these transfers accounted for a little less than 9 percent of its GDP.

Click here to view an interactive chart showing annual remittances received and sent by Caribbean countries and others.

Sources

American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). 2025. Practice Alert: TPS and Parole Status Updates Chart. Updated October 6, 2025. Available online.

Gibson, Campbell J. and Kay Jung. 2006. Historical Census Statistics on the Foreign-Born Population of the United States: 1850-2000. Working Paper no. 81, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC, February 2006. Available online.

Jaupart, Pascal. 2023. International Migration in the Caribbean. Background paper for the World Development Report 2023: Migrants, Refugees, and Societies, World Bank, Washington, DC, April 2023. Available online.

Institute of International Education (IIE). N.d. International Students: All Places of Origin. Accessed September 15, 2025. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). 2024. World Migration Report 2024. Geneva: IOM. Available online.

National Archives Foundation. N.d. Refugee Act of 1980. Accessed October 23, 2025. Available online.

Ratha, Dilip, Sonia Plaza, and Eung Ju Kim. 2024. In 2024, Remittance Flows to Low- and Middle-Income Countries Are Expected to Reach $685 Billion, Larger than FDI and ODA Combined. World Bank blog post, December 18, 2024. Available online.

UN Population Division. 2024. International Migrant Stock 2024 by Destination and Origin. Available online.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2024. 2024 American Community Survey. Access from Steven Ruggles, Sarah Flood, Matthew Sobek, Daniel Backman, Annie Chen, Grace Cooper, Stephanie Richards, Renae Rodgers, and Megan Schouweiler. IPUMS USA: Version 15.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2024. Available online.

—. N.d. 2024 American Community Survey—Advanced Search: S0201 Selected Population Profile in the United States. Accessed October 1, 2025. Available online.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). 2025. Count of Active DACA Recipients by Month of Current DACA Expiration as of December 31, 2024. Updated February 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. Green Card for a Cuban Native or Citizen. Updated August 7, 2025. Available online.

U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP). 2025. CBP Releases December 2024 Monthly Update. Press release, January 14, 2025. Available online.

U.S. State Department, Office of the Historian. N.d. Building the Panama Canal, 1903-1914. Accessed November 6, 2025. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Office of Homeland Security Statistics (OHSS). 2024. 2023 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics. Washington, DC: DHS OHSS. Available online.

Wilson, Jill H. 2025. Temporary Protected Status and Deferred Enforced Departure. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service (CRS). Available online.