By Shasta Scout, Culled from ACoM

The North State’s Mien population took root as families sought escape from an American bombing campaign during the Laotian Civil War. Now, 40 years after resettling, some are at risk of being forcibly returned to a country they have little connection to.

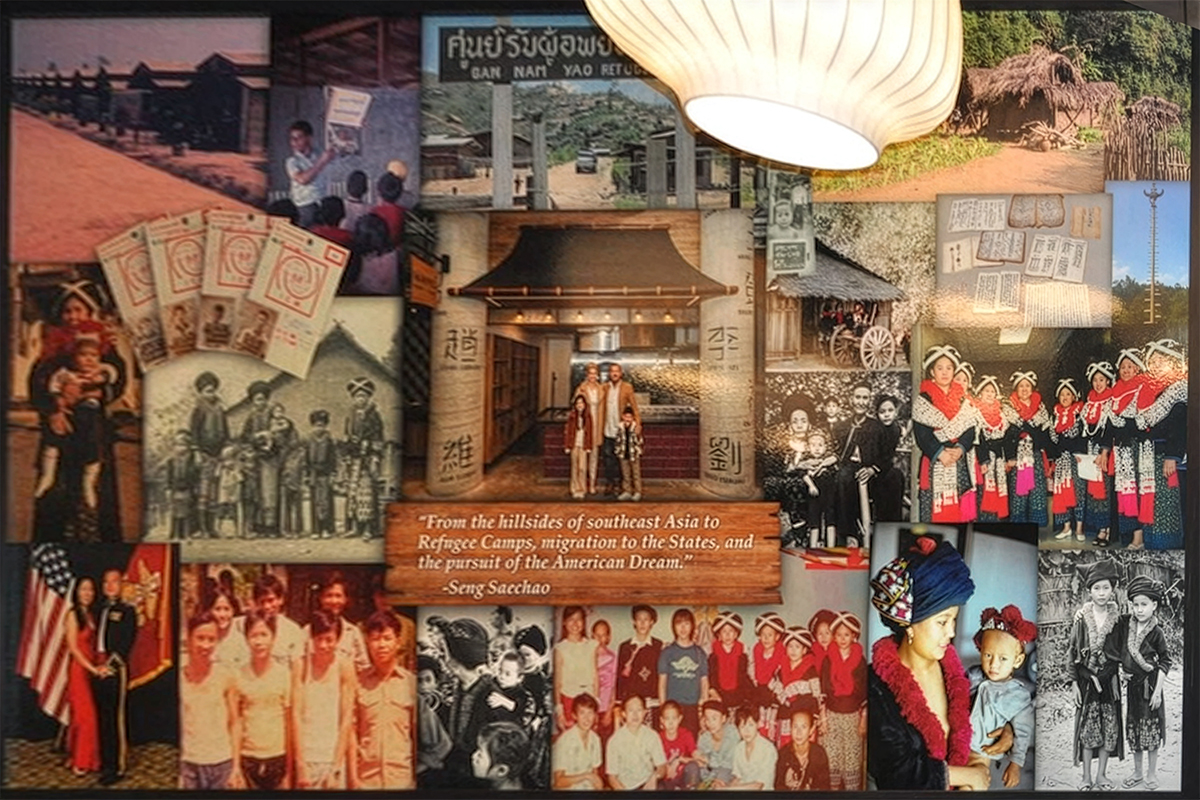

A mural at Redding’s new Public Market commemorates the journey of Mien refugees from Laos to Shasta County. Photo by Annelise Pierce.

By Nevin Kallepalli

REDDING, Calif. — “They flew so low, as high as a tree,” Weun Ayn Lee said, describing the sight of American bomber planes peppering the highlands of Laos a half a century ago. The 58-year old pharmacist, who was just a boy at the time, conjured his memories while speaking with Shasta Scout this month from his home in Redding, California.

It was the 1970s, and President Richard Nixon was overseeing Operation Barrel Roll, a massive aerial bombardment campaign of Laos. All the while, domestic support for the war across the eastern border in Vietnam was rapidly deteriorating, as headlines of U.S.-led massacres shocked the nation. To this day, Laos remains the most-bombed-per-capita country in history with 2 million tons of explosives dropped over nine bloody years. The operation was initially kept secret from the American people, but was revealed by the Pentagon Papers in 1971.

Like other largely rural ethnic minorities splayed across Southeast Asia, the Mien people worked the mountainous terrain of Laos’ countryside, after originally migrating from southern China in the late 19th century. In 1964, three years before Lee was born, President Lyndon B. Johnson ordered the first assault on Laos by air in an unsuccessful attempt to scourge Soviet-armed communists — who would ultimately defeat the CIA-backed Royal Lao Army in 1975. To aid the anticommunist front, the U.S. recruited guerrilla units, including child soldiers, from the Hmong and Mien tribes, the latter of which Lee’s family belonged to.

When the U.S. withdrew from its Laotian proxy war in 1973, the Mien and Hmong were left defenseless against the communist government they had fought at the behest of the Americans. Many were later interned in harsh “re-education camps” where thousands perished. As for Lee, his family ended up in a different kind of camp — a refugee camp in Thailand — after trekking some 10 days to escape reprisals. He was nine.

It was in Thailand that Lee first attended school, though his family only stayed in the camp a few months before finding accommodations with relatives elsewhere. “I remember they didn’t have any houses, anything like that… you had to build your house with some kind of, you know, big leaf from a tree,” he recalled.

Unlike Lee’s family, most Mien who reached refugee camps stayed for years, where some bore children. But despite having Thai-born offspring, entire families remained trapped in perpetual statelessness, unable to seek a higher education or a driver’s license without the citizenship documentation of any country. That is, until the U.S. Congress passed the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act in 1975. With this assistance, more than 400,000 Southeast Asian refugees eventually settled across America. Thus began the Mien, Vietnamese, Hmong, and Khmer communities of Shasta County and the greater North State.

Lee, now a naturalized U.S. citizen who contributes his time to the nonprofit Shasta County Mien Community, says the feeling of insecurity from wandering between nations has never gone away.

He arrived in America as an adult after living in Thailand until he was 19. But for other Mien who came to rural northern California as children, Lee said, the readjustment period was even more difficult. His peers that came earlier had to learn a new language, and use their language skills to take on significant responsibility for their families. “They had to help their parents navigate all the things they had to do to live, like go to the doctor, fill out some kind of form for assistance, or anything like that.”

Over recent decades, the Mien community has made immense strides in the United States, but some who came here as children are now facing the imminent threat of deportation. “They have families, they have kids. All the kids are citizens, their wife is a citizen,” Lee said. “They work, they pay taxes. But now they live in fear. Every day they live in fear that anytime they can be deported to Laos.”

Today, Lee described the Southeast Asian community’s reaction as mixed toward President Donald Trump’s deployment of ICE to crack down on immigrant communities — amid the ramifications being experienced by Mien people.

Refugees at the Lubhini Transit Centre in Bangkok, Thailand. There are about 2,000 refugees in this camp from Cambodia, Vietnam and Laos and they will be going to the United States, Canada, Italy and France. UN Photo/John Isaac. July 1, 1979

Another phase of statelessness

Shasta Scout was unable to directly interview Shasta–based Mien residents at risk of deportation, due to their fears that even an anonymous interview might expose them to expanding surveillance by Immigration and Customs Enforcement. But a non-Mien community member, who provides support to the local Southeast Asian population, attested to the bureaucratic tightrope that some are subjected to.

Trent Copland is a retired educator who taught English as a second language for 30 years at Enterprise High School. In his free time now, he accompanies local Latin American and Southeast Asian immigrants — some of whom are his former students — to their required check-ins with U.S Citizenship and Immigration Services in Sacramento.

Copland’s reason for providing an escort is somewhat practical. He makes the two-and-a-half hour drive each way in his own vehicle to prevent his immigrant contacts from having their vehicles towed in Sacramento should they be unexpectedly arrested during check-in, as has increasingly occurred nationwide. If that scenario plays out, Copland can also act as a liaison to break the news to their families back in Redding. Check-ins are sometimes quick and routine, he said, but other times more menacing. When his immigrant friends have been called inside to face an extended interview with an ICE agent, Copland has at times accompanied them, likening the experience to having a sword held over their head.

“We went into the office and they’re playing good cop, bad cop,” Copland said, recounting the story of a former student’s check-in. “Well, what do you think,” they said, “should we put him in jail? Deport him? Oh, well, you know, he’s got a clean record. Maybe we should let him go. He’s got a wife and a 15 year old daughter,” he continued, mimicking the kind of conversation that can transpire.

For some, the threat of deportation is due to the lingering effects of a crime or crimes they committed — and served time for — many years ago, in their late teens or early 20s.

As Copland observed as a high school teacher in the 1980s, his Mien students’ lives and relationships to authority were extraordinarily complicated. On the one hand, his students from immigrant backgrounds tended to come from stricter and more conservative family structures than their American classmates. On the other hand, some Mien and Hmong teenagers — whose families were mired in poverty after arriving in the U.S. with nothing — joined gangs for a sense of belonging, or later resorted to illicit economies like drug dealing or marijuana cultivation to make fast money.

For some who arrived in the U.S. as children before committing crimes as youth, their specific criminal offenses have affected their immigration status. That’s because when a non-citizen is convicted of certain types of crimes, their refugee status or green card can be revoked, rendering them undocumented upon release from incarceration, and forcing them to effectively begin their refugee or citizenship process over again.

That process is anything but simple, as explained by a DOJ-accredited immigration representative who works with clients across Northern California. They requested to remain anonymous due to fears of being targeted by the federal government. It costs thousands of dollars just to submit the required paperwork for permanent residency, a cost that skyrockets with the addition of legal fees for both criminal and immigration attorneys — structural barriers made even more difficult to overcome amid the stigma of being formerly incarcerated. Some complete the process and others don’t, and many go on to accomplish successful careers and raise American children regardless.

In some instances, incarcerated immigrants aren’t even given the opportunity to remake a life for themselves when they leave state custody. Though California’s sanctuary laws prohibit state law enforcement from coordinating with ICE, in 2022, the ACLU found that the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation “colluded” with immigration enforcement, at times transferring people from state prisons into ICE facilities for indeterminate amounts of time. One of Copland’s contacts was among those transferred from a state prison to a federal prison and detained for years. They declined to speak further for this story, citing safety concerns.

Copeland reflected on the dual realities that while immigrants commit crimes at a much lower rate than American-born citizens, when they do, they may have to pay a much heavier price for their actions. “The punishment has to fit the crime,” Copeland said, assessing the destructive domino effect that follows these immigrants well beyond their convictions and could lead to them being separated from their families, including their spouses and children.

The Facebook group “Returning Laos Foundation” provides insights on the journey Laotian deportees have faced after being forced to leave the U.S. Some ask in comments for information on whether passengers will be shackled on deportation flights, and intel on how to transfer 401k and retirement funds to people who have been expelled from U.S. borders.

Other posts are more reflective. “After days of travel, uncertainty, and waiting, our loved ones are finally on the ground,” one woman wrote about her family landing safely in Vientiane, the capital of Laos. “For some, this is a place they’ve never known, only heard about through stories. For others, it’s a return filled with mixed emotions: relief, grief, fear, and hope all at once.”Nevin reports for Shasta Scout as a member of the California Local News Fellowship.This story is part of “Aquí Estamos/Here We Stand,” a collaborative reporting project of American Community Media and community news outlets statewide.

2025TravelBan #VisaRestrictions #ImmigrationUpdate #KnowYourRights #GreenCardDelays #StudentVisaNews #ImmigrantHelp #LegalAidForImmigrants