L-R: Sandy Close, Paul Chun, Manuel Ortiz, Carlos Aviles, Brenda Verano and Fatima Bakhit

A groundbreaking gathering of ethnic media proves why green spaces are lifelines—and why narrative change is key to park equity.

Magazine, Living Well, The Immigrant Experience

“Almost a million Angelenos don’t have a park within walking distance, and those people are disproportionately Black, brown, and low-income.”

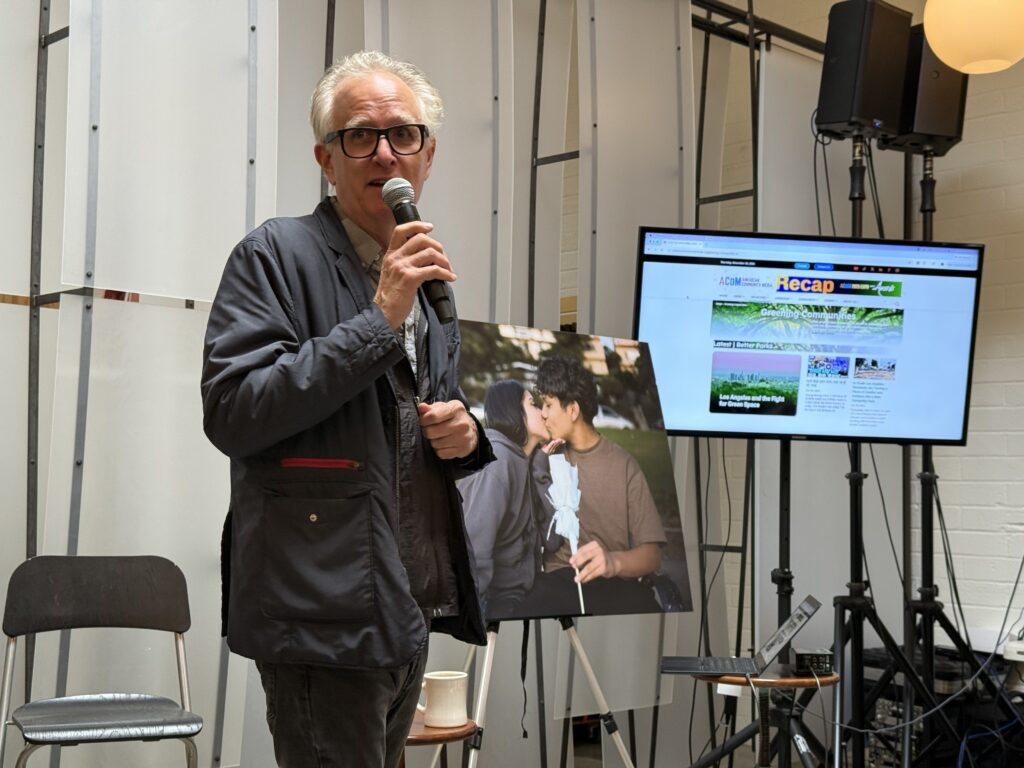

That was the stark assessment shared by Jon Christensen, UCLA professor and director of the Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies, as he opened a vital gathering of journalists and civic leaders at Clockshop in Los Angeles. The November 2025 convening—”Narrative Change Strategies for Parks and Urban Greening”—was more than a panel. It was a public reckoning and strategic reflection on the power of storytelling to influence environmental justice.

Christensen, whose lab partnered with American Community Media (ACoM) and the Bezos Earth Fund, reminded attendees that parks are not just urban niceties—they are indicators of equity. “Environmental changes are perceived, understood, and experienced in divergent ways depending on language, culture, and historical memory,” he said. “Our theory of change is simple but urgent: If journalists can tell more stories about how parks matter, they can move power.”

Welcome by Jon Christensen, UCLA Laboratory for Environmental Narrative Strategies.

This convening followed the 2025 Greening Communities Reporting Initiative, a groundbreaking collaboration that brought together 22 reporters representing ethnic and community media outlets across Southern California—most based in Los Angeles. Working in Spanish, Korean, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Farsi, Arabic, Burmese, and more, these journalists produced 77 original pieces: 57 in print and online, 12 television broadcasts, and 8 audio stories. Their collective work reframed parks as essential infrastructure for health, joy, protest, and identity.

This wasn’t just a retrospective on powerful stories told. It was a strategy session for the future—especially with a 2026 parks bond on the horizon. At a time when ethnic media is too often left out of mainstream environmental discourse, this convening centered them—showcasing their role not as peripheral messengers, but as frontline narrators shaping civic consciousness.

“We don’t tell people how to vote,” said Sandy Close, Executive Director of ACoM, who moderated the event and shaped its narrative urgency. “But we do tell them what’s at stake. Parks are not background. They’re frontlines. They’re where community happens.”

Close, a pioneer in building coalitions across ethnic media, helped lead five media briefings that informed the reporting initiative, giving reporters access to experts, advocates, and community members across LA’s diverse neighborhoods. “This project has never been about top-down storytelling,” she said. “It’s about letting communities shape their own environmental narratives and be heard—especially in civic debates that too often ignore them.”

The result was a mosaic of stories that transformed how journalists approached environmental narratives—starting with their own understanding.

Take photographer Manuel Ortiz, for instance. Best known for documenting immigration raids and war zones, Ortiz approached his park assignment with hesitation. “I didn’t like LA,” he said. “But I found a new Los Angeles in the parks. People praying, sleeping, stretching, talking, and resisting. For them, this wasn’t recreation. It was ritual.”

Ortiz traveled light—one camera, one lens, no zoom. “It forced me to be close,” he said. “I asked three questions: Who are you? What are you doing here? What does this park mean to you?” He expected complaints. Instead, he found stories of salvation. A man in a wheelchair told him, “I come here every day. If I didn’t, I don’t know if I’d still be here.” Ortiz titled his series Green Sanctuaries.

Brenda Verano, who reported for CALÓ News and the LA Blade, said the project reshaped her relationship with her community—and her craft. “I live in South Central. We have more liquor stores than parks,” she said. “So I was intentional about focusing on the places I know.”

She profiled South LA Park and South LA Wetlands Park—spaces vital to the neighborhood but too often neglected. When she uncovered a $4.2 million beautification grant for Wetlands Park that had gone unannounced, she pushed the councilmember for comment. “He released a statement the day before my story was published,” she said. “That’s the power of local media.”

Her stories didn’t just capture policy. They captured people. “I spoke with la señora who walks to the park every morning. The youth, organizing a community patrol. Parks in South Central are not just for play. They’re for protection.”

Paul Chun of SBS International brought the Koreatown perspective, one shaped by density and history. “Koreatown is the second most densely populated neighborhood in the country after Manhattan,” he said. “We have almost no green space. It’s been a problem for decades.”

Through his reporting, Chun interviewed residents, city officials, and LA’s parks director, who is himself Korean American. He learned that some upgrades were coming in preparation for global events like the 2028 Olympics. But what struck him most was Seoul International Park. “It’s where the 1992 peace march began after the LA riots,” he said. “Today, it hosts the Korean Festival, drawing over 400,000 people. That park is sacred ground for us—culturally, historically, and emotionally.”

Fatmeh Bakhit, publisher of the Arabic-language El Enteshar, brought a generational lens. Living near Griffith Park, she said her children—and even her late father—benefited from daily access to green space. But that access isn’t universal. “Most Arab families I interviewed live in North Hollywood or Orange County,” she said. “They don’t have parks nearby. And it matters.”

Her reporting spotlighted how parks serve as rare gathering grounds. “We do our Eid prayers in Glendale’s Pacific Park,” she said. “Thousands come. We dance, eat, and connect. It’s our cultural center. We need more places like that.”

Carlos Aviles, editor at Excélsior and contributor to the San Diego Union-Tribune, traced the evolution of Hazard Park. “Twenty years ago, it was a hotspot for gang activity,” he recalled. “Now, it has soccer teams and mentorship programs. One woman I interviewed used to be approached by gang recruiters. Now her kids are recruited for baseball.”

He also echoed a recurring theme: safety. “In South LA, it’s not just about having a park,” he said. “It’s about whether you feel safe using it.”

As the convening closed, each speaker reflected on how ethnic and community media play a bridge role—not just between audiences and information, but between communities and decision-makers.

Christensen called for continued investment. Close urged deeper collaboration. Chun called for long-term solutions in Koreatown. Verano pushed for more support for independent reporters. Bakhit called for accessible, inclusive park design. Ortiz reminded us that the stories are already there—waiting to be seen.

What united them was clarity: in a city divided by concrete and class, parks are where people come together—often in defiance, always with hope.

#GreenEquity #EthnicMediaVoices #LAParksMatter #UrbanJustice #CommunityPower #ParksAreEssential #NarrativeChange #ImmigrantStories #PublicSpaceJustice #GreeningCommunities