This post was originally published on this site

Employment Verification: The Next Front for U.S. Immigration Enforcement?

A person uses a digital tool to screen a job applicant. (Photo: Napong Rattanaraktiya/iStock.com)

E-Verify, the federal system for authenticating an individual’s right to lawfully work in the United States, was once heralded as the silver bullet to control unauthorized immigration. But expanded use of the online platform has taken a back seat at the federal level for many years, while making some small gains in states. There are, however, signs that employment verification could draw renewed attention from federal policymakers. Given the Trump administration’s relentless focus on deporting unauthorized immigrants, Washington’s lack of action on expanding employment verification may become starker.

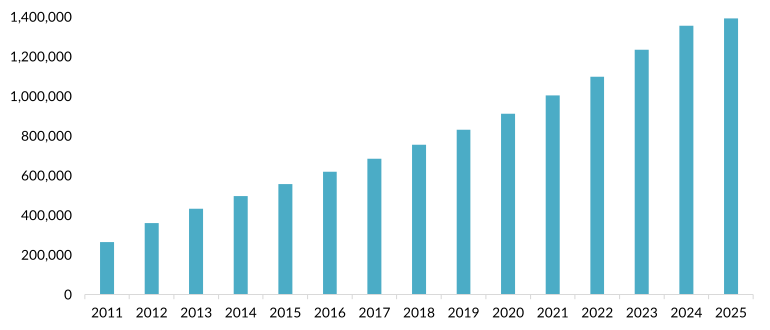

A nearly 30-year-old, mostly voluntary program, E-Verify promises employers the ability to determine whether an individual is lawfully authorized to work. Nearly 1.4 million U.S. employers used the system as of mid-2025, accounting for just less than one in six employers nationally, suggesting the program has fallen short of its supporters’ goal. The Migration Policy Institute (MPI) estimates that as of mid-2023 more than 9 million workers were unauthorized immigrants, though a subset held a work permit as the result of having been granted Temporary Protected Status (TPS), other deferred action or humanitarian parole, or having a pending asylum case.

At the federal level, some members of Congress have focused on making E-Verify mandatory for all hiring nationwide, with introduction of bills in the House and Senate to that effect earlier this year. Yet these kinds of efforts have failed to advance in the past, and conversations about alternative approaches to E-Verify, which has noted weaknesses, have stalled for the most part.

There has been much more activity at the state level. Since the program’s inception, lawmakers in 21 states have enacted laws to order or expand use of E-Verify. The requirements have come in different permutations, including mandated employment verification for state contractors or all employers exceeding a certain number of workers.

Curiously, the Trump administration’s stance on the program is at best ambivalent, even as the ability to work legally for an increasing number of immigrants is in flux with its termination of some grants of TPS and humanitarian parole, which allow recipients to work lawfully. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) has issued guidance urging employers to use E-Verify to check their new hires. Yet at the same time, the department has criticized employers for relying solely on E-Verify to determine individuals’ right to work.

To be sure, business groups have long criticized E-Verify, citing errors in the program’s ability to detect identity fraud. But the failure of E-Verify to meet its promise has also been due to longstanding shortcomings of the program itself, primarily its inability to confirm that the person presenting a document for verification is the one to whom it was issued. In other words, while E-Verify can successfully confirm documents are legitimate, it is unable to connect those documents to actual people. Similarly, employers and labor advocates have long complained that the system produces false negatives, including if a person’s name is misspelled or updated after they get married, naturalize, or undergo other life events.

While employment verification provides the basis for the government to hold accountable businesses that hire unauthorized workers, in reality almost all worksite enforcement across both Democratic and Republican administrations has been directed at workers, not employers.

This article outlines the state of play on E-Verify, reviews its history, and examines the uneven enforcement record.

Rooted in the fact that many unauthorized immigrants are drawn to the United States by the opportunity to work, Congress in 1986 passed the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which for the first time penalized employers who knowingly hire unauthorized immigrants. In doing so, it set up a verification process that employers must follow to hire all new workers—a system that still exists today. With the federal I-9 form, the employer and employee both attest that the worker is able to work legally and that the documents proving this authorization appear genuine. All employers must retain signed I-9s for a period of time depending on the worker’s employment status. Failure to comply can result in civil fines for employers.

This process was meant to deter hiring of unauthorized workers. However, its effectiveness was quickly tested. In practice, the I-9 process has been plagued by a proliferation of fraudulent documents. While some good-faith employers unknowingly accept fraudulent documents, those acting in bad faith can also hire unauthorized workers and plead ignorance, since the law holds them responsible only for knowingly hiring people without work authorization.

Given the pervasive use of fake IDs and the “knowingly” loophole, Congress introduced pilot programs for database-driven employment verification in the 1996 Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA). The Basic Pilot was launched in 1997 in California, Florida, Illinois, Nebraska, New York, and Texas; in 2003, it was expanded to all 50 states. From 1997 to 2005, the program remained small, with fewer than 5,000 participating employers. In 2005, the George W. Bush administration sought to strengthen and reform the program, which in 2007 was renamed E-Verify. For more than a decade, usage has increased, but the share of total employers utilizing E-Verify remains small: As of June 30, 2025, just 14 percent of all U.S employers participated.

Figure 1. Number of U.S. Employers Participating in E-Verify, 2011-25

Source: U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), E-Verify, “History and Milestones: Chronological Summary of the Milestones of the E-Verify Program,” updated December 31, 2024, available online.

The program is voluntary for most employers, except federal contractors or subcontractors, those previously convicted of violations, and others required by state law to participate. It is meant to complement the I-9 process. Employers enter biographic information from the I-9 form into the E-Verify system, which is administered by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), and the information is compared to federal databases, including DHS and Social Security Administration (SSA) ones. In some states, I-9 information is also compared with state databases such as those for driver’s licenses. If the screening reveals a match, E-Verify notifies the employer that the individual is authorized to work. If not, E-Verify provides the employer with a temporary non-confirmation (TNC) notice, and the employee can contact DHS or SSA to resolve the issue. If they fail to do so, E-Verify will issue a final non-confirmation (FNC) notice and instruct that the employee be terminated.

Figure 2. The E-Verify Process

Source: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) rendering.

USCIS has regularly sought to improve E-Verify and make it more user-friendly, including by automating systems and shortening processing times. The platform has become better at identifying fraudulent documents, but there still are glaring problems, particularly its inability to tie a document to the individual presenting it—leaving open the opportunity for workers to use documents that do not belong to them. Moreover, the system is not foolproof, and workers who are legally authorized to work, including U.S. citizens, have at times received false negatives.

E-Verify has also been criticized for lacking a contingency plan in the event of technical challenges. Most recently, E-Verify was offline from October 1 to October 9 due to the government shutdown, and employers using the program faced delays confirming new hires’ work authorization. During the government shutdown in 2018 and 2019, E-Verify remained offline for the entire period.

Although it is mostly a voluntary program, E-Verify has been mandated by many states for some businesses. For state leaders who want to be seen as cracking down on unauthorized immigration, E-Verify mandates are a readily available avenue. Ten states mandate the use of E-Verify for all or most employers and another 11 require E-Verify for public employers or contractors (see Figure 3). Several counties in Washington State also require its use for certain contractors or workers, although there is no statewide law.

Conversely, California and Illinois restrict the use of E-Verify. In California, it is illegal for the state, cities, counties, or special districts to mandate the use of E-Verify (this does not apply to federal contractors or subcontractors), though employers can use the program voluntarily. In Illinois, employers can use E-Verify if they want but must meet specific state requirements, including mandatory program training and reporting requirements to employees.

Figure 3. State Requirements on Employers’ Use of E-Verify, 2025

Note: Washington State does not have state requirements for E-Verify but several counties in the state require its use. The state’s categorization in the figure reflects those county requirements.

Source: John Fay, “2025 E-Verify State Requirements,” Equifax, updated February 2025, available online.

The courts have consistently upheld states’ ability to regulate use of E-Verify. For example, a landmark 2011 Supreme Court decision upheld an Arizona law requiring employers to use the program. Just this year, a federal judge in Illinois dismissed a case brought by the Trump administration claiming the state’s restrictions discouraged use of E-Verify and interfered with the federal government’s enforcement of immigration laws.

These laws appear to influence how many businesses participate in E-Verify. The largest number of participants as of June 2025 was in Georgia (165,000), with significant participation across the Southeast and elsewhere in states requiring use by all or most employers.

Figure 4. Number of Employers Participating in E-Verify, by State, 2025

Source: DHS, E-Verify, “E-Verify Usage Statistics,” updated June 30, 2025, available online.

However, state enforcement is often lacking. For instance, although Arizona mandates use of E-Verify, violators face minimal penalties. Since the Legal Arizona Workers Act (LAWA) went into effect in 2008, just three companies have faced fines for employing unauthorized workers and none faced criminal prosecution.

In some states, lawmakers are at odds about whether to mandate E-Verify use. For example, in Texas, legislative efforts to mandate E-Verify use for all employers have repeatedly failed. The resistance is partly based in opposition to regulating employers and also seems linked to the fact that many Texas companies rely on unauthorized workers.

Since E-Verify’s inception as a pilot program in 1997, every term of Congress has seen bill introductions mandating broader or universal use. All have failed to become law. Recent attempts in 2025 include the Legal Workforce Act, introduced by Representative Ken Calvert (R-CA) in January; the Accountability through Electronic Verification Act, introduced by Senator Charles Grassley (R-IA) in March; and the Day 1, Dollar 1 E-Verify Act, introduced by Representative Ryan Mackenzie (R-PA) in April.

Business leaders, who successfully have limited the reach of IRCA’s employer sanctions, have long led the resistance to mandatory E-Verify use. But the business community has heightened concerns today, amid the Trump administration’s quest for mass deportations, vastly increased funding for ICE, and the restructuring of USCIS to prioritize fraud detection. There is mounting belief that aggressive immigration enforcement and more hostile government rhetoric are discouraging unauthorized immigrants from working, sparking widespread economic repercussions.

The administration’s mixed messaging adds to these concerns. As the Trump administration terminated various programs allowing some unauthorized immigrants with liminal (temporary) statuses to obtain work authorization, DHS issued guidance to employers to regularly recheck employees’ status using E-Verify. MPI estimates that as many as 4 million unauthorized immigrants—not all of them of working age—held a “twilight” status such as TPS or humanitarian parole as of mid-2023. Many of these individuals have lost authorization to work with the administration’s termination of certain TPS designations and parole programs such as the Cuban, Haitian, Nicaraguan, Venezuelan (CHNV) program. With the cancellation of these statuses, employers now find themselves unsure who has work authorization and who does not.

Yet the administration has also suggested that E-Verify is not sufficient to check employees’ right to work. For instance, the police department in Old Orchard Beach, Maine was recently found to have hired an officer who lacked valid work authorization but had nonetheless been cleared by E-Verify; in response, DHS spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin called the police department’s reliance on E-Verify “reckless.” While simultaneously urging use of E-Verify and reprimanding businesses for relying on its inaccurate results, the administration has placed good-faith employers in a difficult position.

Amid Patchwork Landscape, Enforcement Has Focused on Individuals, Not Businesses

Despite White House statements indicating that employers who hire unauthorized immigrants will be held accountable, since January 2025 enforcement has primarily focused on unauthorized workers—as it has historically. Although data on the exact number of worksite enforcement operations are unavailable, a Washington Post analysis of ICE news releases found that only one of the worksite enforcement operations occurring from January to June led to an employer facing charges; all others resulted in worker arrests and likely subsequent deportations. In April, ICE reported that it had arrested more than 1,000 unauthorized workers from January to April and imposed more than $1 million in employer fines. If this pace persists, employer fines for this year would be well below the average $33.6 million civil and criminal fines issued annually from fiscal year (FY) 2005 to FY 2023, the most recent data available.

Most reported worksite enforcement operations occur at small businesses such as restaurants, car washes, or construction sites, and each recent enforcement action typically has yielded fewer than 100 arrests. However, this administration has also carried out several high-profile worksite operations, including in September at the Hyundai battery plant in Ellabell, Georgia, which resulted in the detention of nearly 500 workers, mostly from South Korea. More than 300 Korean nationals were quickly deported—though it has since emerged that many were lawfully present. While ICE initially trumpeted the operation as the single biggest single-site one ever, the rhetoric has been dialed down amid tensions with South Korea over future business investments in the United States and the expected filing of a class-action lawsuit by many workers.

Worksite enforcement priorities have varied from administration to administration. After worksite enforcement operations were deemed largely ineffective in the 1990s, several high-profile ones were conducted during the George W. Bush administration. Perhaps most visible was one at the Agriprocessors meatpacking plant in Iowa, which involved more than 900 federal agents and resulted in the arrest of 389 workers. The Obama administration took a different approach, largely focusing on I-9 audits. During the first Trump administration, worksite enforcement increased under the direction of acting ICE Director Tom Homan; from 2017 to 2019, more than 1,800 workers were arrested. In 2021, the Biden administration halted worksite enforcement operations in favor of I-9 audits.

Still, regardless of each administration’s priorities, there has been a consistent imbalance in worksite enforcement. Employers often come away unscathed or with minor fines, while workers lose employment and/or face deportation. This imbalance is due in part to IRCA itself, which establishes a high burden of proof to prosecute. The political influence wielded by certain business sectors also comes into play. For example, the Trump administration in mid-2025 briefly paused operations on farms, in hospitality, and in food processing after industry outcry, though such operations have seemingly resumed.

From 2005 through 2023 (the most recent year for which data are available), more than three times as many employees were arrested during worksite operations as employers (see Figure 5). There are no complete data on how many of these arrests led to prosecutions, but the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) found in 2019 that in most years since 1986, fewer than 15 employers were prosecuted annually; of those prosecuted, even fewer were convicted of crimes leading to prison sentences, while most typically faced fines.

Figure 5. Worksite Enforcement Arrests, Civil Fines, and Criminal Fines, FY 2005-23

Note: Fiscal year (FY) 2023 is the most recent year for which data are available.

Sources: DHS, Border Security Status Report: Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress (Washington, DC: DHS, 2016), available online; DHS, Border Security Status Report: Fiscal Year 2023 Report to Congress (Washington, DC: DHS, 2025), available online.

Sholom Rubashkin, the owner of the Agriprocessors meatpacking plant targeted in 2008, was a rare corporate leader to face a significant prison term because of worksite enforcement (he was convicted of multiple financial crimes). President Donald Trump, however, commuted Rubashkin’s 27-year sentence in 2017, after eight years served in prison.

Shaping the Future of E-Verify

Increased worksite enforcement may bring E-Verify back into the national conversation. Over the last decade, most attention on employment verification has occurred below the federal level, with states setting conditions to mandate or restrict its use. Some in Congress have continued to lead the call for a national mandate, but with little traction.

Scrutiny over the hiring of unauthorized workers seems to have ramped up under the Trump administration, with a proliferation of worksite enforcement operations impacting small businesses and large corporations alike. Yet the administration’s comments on E-Verify have left employers puzzled.

If Congress and the administration are serious about using E-Verify in combination with worksite enforcement to prevent the hiring of unauthorized workers, they cannot depend on state rules alone. The effort will need to be a serious national enterprise, which cannot succeed unless the well-documented drawbacks, vulnerabilities, and inefficiencies in the E-Verify system are addressed. Experts have long suggested that innovations in technology should be used to strengthen pervasive program weaknesses. Federal leaders might want to consider how to make the system more efficient and responsive, while also penalizing employers acting in bad faith. The future of employment verification and the E-Verify program itself will likely depend on whether this moment of renewed focus translates into meaningful modernization.

The authors thank Allison Rutland for research assistance.

Sources

American Immigration Council. 2025. Understanding ICE Raids at American Workplaces. Washington, DC: American Immigration Council. Available online.

Bier, David, J. 2019. The Facts about E‑Verify: Use Rates, Errors, and Effects on Illegal Employment. Cato Institute blog post, January 31, 2019. Available online.

Fay, John. 2025. 2025 E-Verify State Requirements. Equifax, February 2025. Available online.

Gelatt, Julia, Ariel G. Ruiz Soto, and James D. Bachmeier. 2025. Changing Origins, Rising Numbers: Unauthorized Immigrants in the United States. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI). Available online.

Hansen, Ronald J. 2025. This Arizona Law Was Supposed to Stop Illegal Labor. Why Employers Often Ignore It Anyway. The Arizona Republic, January 19, 2025. Available online.

Hughes, Trevor and Lauren Villagran. 2025. Hyundai Battery-Factory Raid Reveals New Trump Target: Employers Who Hire Illegal Workers. USA Today, September 9, 2025. Available online.

Kriel, Lomi. 2025. Texas Won’t Force Private Companies to Use E-Verify to Check Workers’ Immigration Status, Despite Leaders’ Tough Talk. The Texas Tribune, June 25, 2025. Available online.

LeVine, Marianne, Lauren Kaori Gurley, and Aaron Schaffer. 2025. ICE Is Arresting Migrants in Worksite Raids. Employers Are Largely Escaping Charges. The Washington Post, June 30, 2025. Available online.

Mayorkas, Alejandro N. 2021. Worksite Enforcement: The Strategy to Protect the American Labor Market, The Conditions of the American Worksite, and the Dignity of the Individual. Memorandum from the Acting Secretary of Homeland Security to Tae D. Johnson, Acting Director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE); Ur M. Jaddou, Director of U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS); and Troy A. Miller, Acting Commissioner of U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), October 12, 2021. Available online.

Meissner, Doris and Marc R. Rosenblum. 2009. The Next Generation of E-Verify: Getting Employment Verification Right. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Middleton, Gordon. 2024. Navigating E-Verify: State by State Mandates. Experian blog post, November 11, 2024. Available online.

Moodie, Alison. 2025. Trump’s Mixed Messaging on Immigration Raids Leaves Employers Uncertain. Boundless Immigration blog post, July 24, 2025. Available online.

Ogletree Deakins. 2011. Supreme Court Upholds Arizona E-Verify Law. May 31, 2011. Available online.

Reyes, Adriana and Brian Graham. 2025. E-Verify Update: New Guidance for Employers on EAD Revocations. K&L Gates Hub, September 12, 2025. Available online.

Rosenblum, Marc R. 2011. E-Verify: Strengths, Weaknesses, and Proposals for Reform. Washington, DC: MPI. Available online.

Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). 2019. Few Prosecuted for Illegal Employment of Immigrants. Updated May 30, 2019. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). 2016. Border Security Status Report: Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

—. 2025. Border Security Status Report: Fiscal Year 2023 Report to Congress. Washington, DC: DHS. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), E-Verify. 2024. History and Milestones: Chronological summary of the milestones of the E-Verify Program. Updated December 31, 2024. Available online.

—. 2024. What Is E-Verify. E-Verify, updated October 24, 2024. Available online.

—. 2025. E-Verify Resumes Operations. E-Verify, October 9, 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. E-Verify Usage Statistics. Updated June 30, 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. New “Status Change Report” for E-Verify Users following Parole Termination and EAD Revocation. E-Verify, June 20, 2025. Available online.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS), Study in the States. N.d. Understanding E-Verify. Accessed November 10, 2025. Available online.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). 2025. ICE Arrests Over 1k Illegal Workers, Proposes $1M in Fines. Press release, April 15, 2025. Available online.

Ward, Vicky. 2019. The Inside Story of How a Kosher Meat Kingpin Won Clemency Under Trump. CNN, August 9, 2019. Available online.

Wiessner, Daniel. 2025. U.S. Judge Rejects Trump Administration Challenge to Illinois E-Verify Law. Reuters, August 20, 2025. Available online.