This post was originally published on this site

Government Efforts to Boost Diaspora Remittances Earn Mixed Results

A woman receives a cash transfer in Sierra Leone. (Photo: Dominic Chavez/World Bank)

Each year, emigrants and other diaspora members send hundreds of billions of dollars of their own money back to family and friends in their homelands. The amount of money sent to loved ones in low- and middle-income countries as remittances—an estimated $685 billion via formal channels in 2024—is much larger than all official foreign aid and represents a critical economic pillar for many receiving communities.

Aware of this potential, some countries with large diasporas—emigrants and later generations with ancestral links to the country—have sought to maximize incoming remittances and channel some of the money transfers away from households and into particular sectors, often through matching programs. In recent decades, a growing number of governments have implemented diaspora engagement policies to mobilize transnational resources to support long-term national development.

For example, remittances accounted for approximately two-thirds of Nepal’s economy in 2024, according to World Bank data, and the government has pursued policies to channel diaspora resources toward productive investments. This includes encouraging transfers that support the industrial sector, community development projects, and local infrastructure programs, often through co-financing arrangements with the state. A key instrument in this strategy has been the 2008 Non-Resident Nepali Act and subsequent policy frameworks.

Adoption of formal diaspora engagement policies globally has generally increased over time, although a small number of governments have scaled them back. Many policies have the primary objective of boosting remittance inflows to provide economic stimulus; however they often pursue additional goals such as facilitating the transfer of skills and technology or attracting investments through business ventures or funding start-ups.

The intangible impacts of these policies—such as in diaspora members’ personal connections to their homeland or the country’s international image—are impossible to quantify. But when it comes to monetary impact, evidence suggests that countries with diaspora engagement policies generally receive more remittances than those without them. Research by the author found that, during the 1996-2022 period, countries with these policies for which sufficient data were available received on average about 2.2 percentage points more remittances as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) than those without. A separate study by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) found that countries with dedicated diaspora or emigration policies received more than twice as many remittances measured as a share of GDP (7.3 percent compared to 3.3 percent in 2022).

However, remittance trends are also shaped by broader economic and political contexts beyond the reach of individual countries’ diaspora engagement. Rising inflation may dampen remittance sending and political instability, conflict, or natural disasters can also affect senders’ behavior, among other factors. Policies in migrants’ host countries may also play a role; while the full impact is as yet unknown, the United States under the Trump administration has increased immigration enforcement and will impose a new 1 percent tax on remittances, which may affect how much money diaspora members transfer.

This article describes governments’ approaches to increase remittance sending by their diaspora.

Remittances as Lifelines: Misconceptions, Realities, and Policy Responses

Many migrants and other diaspora members carry the responsibility of supporting their family in their country of origin, often through the transfer of remittances. These financial outflows are derived entirely from individuals’ personal earnings and operate like any other personal expenditure. For those who receive the money, remittances function as a vital lifeline for households and, as a result, communities. They frequently alleviate poverty and provide a cushion during periods of economic hardship, in turn helping the economy. In Nepal, Tajikistan, Nicaragua, Samoa, Bermuda, and Honduras, remittances sent via formal channels formed more than one-quarter of overall GDP in 2024.

Survey data underscore the important role remittances serve. Approximately 80 percent of migrants from Latin America and the Caribbean reported from 2014 to 2021 that their remittances were primarily directed toward household maintenance, including essential daily expenses such as food, housing, and transportation. In northern Central America, 86 percent of remittance-receiving households used the money to buy food, according to a 2021 Migration Policy Institute (MPI) and World Food Programme study, while 40 percent spent the money on health issues and 30 percent put it to utility bills. Many recipients also direct remittances toward education, savings, and investment.

Even as remittance outflows represent the movement of individuals’ own resources, leaders of some remittance-sending countries perceive them as a resource that is being siphoned away from their own economies and have made efforts to restrict or regulate these transfers. For example, the United States, which hosts more international migrants than any other country, has long been the top source of international remittances globally, accounting for about $93 billion sent via formal channels in 2023, according to World Bank data. The Trump administration imposed limits on family remittances to Cuba in 2019, during its first term; earlier this year, Congress created a new 1 percent tax on many types of outgoing international money transfers, which will go into effect in 2026.

Many countries have pursued strategies to increase remittance inflows and other connections to their diasporas, recognizing their profound economic and social significance. Broadly speaking, such policies can be grouped into two categories: hard economic measures and soft engagement strategies.

Hard measures are designed to facilitate financial flows and investment, often through mechanisms such as reducing remittance transfer costs, issuing diaspora bonds, establishing preferential banking channels, or implementing matching programs that encourage greater capital inflows. For instance, since 2015 Mexico has authorized tens of thousands of convenience stores and other shops to be “banking agents” where individuals can easily send or withdraw cash, easing the flow of remittances and helping recipients transition from using cash to electronic mobile payments. Mexico also launched a program, Tres por Uno (3×1), that provides a $3 match from the federal, state, and local government for every dollar remitted by diaspora associations, with the resulting funds invested in development projects agreed by local residents and migrants. Malawi’s diaspora engagement policy, unveiled in 2017, emphasizes attracting investment and remittances by providing incentives, reforming access to land, and conducting promotional campaigns.

Additionally, several countries have offered diaspora bonds, allowing members of the diaspora to temporarily loan the government money with a fixed rate of return. Nigeria offered its first diaspora bond in 2017, enabling investors with Nigerian heritage who lived abroad to receive a financial return while also channeling funds toward national development projects. The country raised nearly $300 million with the bond, which was significant but nonetheless well below the $22 billion that arrived via formal remittances that year, and has considered launching a new bond in the near future.

Soft engagement strategies, meanwhile, seek to strengthen political and cultural ties. These may include extending dual citizenship, granting voting rights to nationals living abroad, or organizing cultural and professional conventions. Ethiopia’s “yellow card” identification policy demonstrates such an approach; holders of the ID card can travel and live visa-free and own property in Ethiopia, among other benefits.

Despite countries’ adoption of diaspora engagement policies, the direct impact of these policies on remittance flows is neither clearly established nor absolute. Frequently, governments adopt economic-focused diaspora policies under the assumption that remittance increases will naturally follow, without systematically measuring the outcomes. Governments often cite as evidence anecdotal indicators, such as higher remittance volumes, spikes in diaspora tourism, or participation in cultural events. Yet it is typically unclear the extent to which these outcomes can truly be attributed to the policies themselves, and difficult to create credible metrics to measure policy impact in this area.

Still, there does seem to be a link. Many countries have experienced an increase in average remittance inflows following the implementation of diaspora engagement policies. For instance, remittances accounted for less than 9 percent of Nepal’s GDP on average in the ten years before the 2008 unveiling of its first diaspora policy; in the subsequent decade, remittances accounted for an average of 24 percent of GDP.

To be sure, the presence of a formal policy does not automatically guarantee higher remittances. While El Salvador and the Philippines have invested heavily in various efforts to benefit from emigration, they do not have formal diaspora engagement policies as defined by the EU Global Diaspora Facility. Yet they have recorded higher inflows sent by official channels (an average of 19.9 percent and 10.2 percent of GDP, respectively, across the 2000-24 period) than some countries with those policies, including Mexico (2.5 percent) and Ethiopia (1.1 percent).

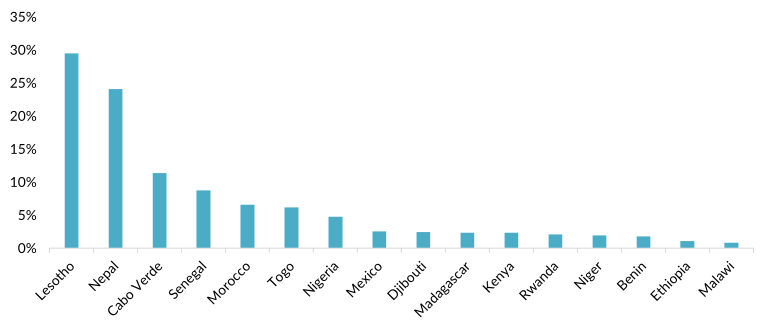

Figure 1. Average Annual Remittance Inflows as a Share of GDP in Select Countries with Diaspora Engagement Policies, 2000-24

Source: Author’s analysis of World Bank, “Personal Remittances, received (% of GDP),” updated October 7, 2025, available online.

While diaspora engagement policies may create enabling environments for remittance flows through improved financial infrastructure and stronger connections with the homeland, the policies’ effectiveness is highly contextual and insufficient as standalone interventions.

Countries with larger economies tend to have lower relative remittance inflows as a share of GDP, even if the transfers are sometimes large in absolute terms. These countries therefore may not necessarily perceive financially minded diaspora engagement policies to be priorities.

Inflation, Political Stability, and Other Factors

Similarly, an increase in inflation in remittance-receiving countries seems to be associated with a slight decrease in remittance inflows as a share of GDP. The relationship is complicated, however, and studies yield divergent conclusions. Some studies suggest higher inflation in remittance-receiving countries drives increased remittances, while others argue that remittance inflows themselves contribute to inflation. Additionally, depreciation of the remittance-receiving country’s currency can reduce the amount of money that is transmitted, as fewer foreign dollars (or euros, or another currency) are required to purchase the same basket of goods.

Political stability also seems to impact remittance inflows, but not in obvious ways. Many scholars associate higher political stability with increased inflows in both the short and long term. In Turkey, for instance, years of political violence in the 1970s saw a relatively lower level of incoming remittances than during periods of calm. Yet alternative perspectives highlight that deteriorating socioeconomic conditions and upticks in political corruption can also spur incoming remittance transfers, as individuals abroad seek to assist their families in increasingly precarious times. This dynamic was observed in one study covering 22 sub-Saharan African countries from 1994 to 2015, in which researchers speculated that remittances were partly motivated by senders’ altruistic desires to mitigate loved ones’ challenges. The drivers of remittance behavior, therefore, are often context-dependent and may operate in opposing directions.

Conditions in remittance-sending countries also shape how much money is sent. Economic downturns that cause diaspora members to lose their jobs can reduce the amount of money they send back. Heightened immigration enforcement can also play a role, as illustrated by recent developments in the United States. Following statements and policy directives by the Trump administration targeting unauthorized immigrants, the largest numbers of whom originate from Mexico, remittances to that country declined by nearly 6 percent over the first eight months of 2025 compared to the same period in 2024, as many individuals avoided work and other public settings. Conversely, in response to these same threats, some Central Americans resident in the United States have increased the amount of funds they have sent to the homeland, seemingly to secure the financial wellbeing of their families before they are possibly arrested and deported.

Harnessing Diaspora Engagement

Even if impacts of diaspora engagement on financial remittances vary and are affected by other factors, such policies serve other important purposes beyond direct financial ones. For instance, Mexico’s Red Global MX attempts to use the skills in its diaspora to develop the country’s knowledge-based economy. Meanwhile, Morocco’s Operation Marhaba (meaning “welcome and attraction” in Arabic) is a seasonal initiative that manages peak return migration, providing administrative and other support to returning members of the Moroccan diaspora during summer holidays.

These examples illustrate that even if diaspora-focused policies do not directly guarantee increased remittances, they can help foster social, cultural, and economic engagement between diasporas and their homelands. By combining outreach, financial incentives, and coordinated government services, such policies create structured opportunities for diasporas to contribute to national development while maintaining strong connections with their homeland.

Mutual Benefits

Remittances have wide benefits and are an expression of personal financial choices. Importantly, these transfers do not cost taxpayers or the government in the remittance-sending country; rather, they may incentivize diaspora members to work harder and earn more money to invest both locally and abroad.

Viewed this way, remittances create a mutually beneficial scenario in which host countries benefit from migrants’ labor, skills, and economic contributions—which are particularly vital in aging populations across Europe, North America, and parts of Asia—while homelands receive essential financial, social, and human-capital support.

Rather than imposing restrictions on outgoing transfers, governments might seek to strengthen this mutually beneficial relationship through initiatives such as skilled worker programs, educational exchanges, or by facilitating investment. When optimized to support transnational engagement, remittances become more than personal money transfers; they can transform into builders of sustainable economic growth, social development, and stronger ties between host and origin countries.

Sources

African Foundation for Development (AFFORD). 2020. Diaspora Engagement Mapping: Ethiopia. Brussels: European Union Global Diaspora Facility (EU-DiF). Available online.

Ajide, Kazeem Bello and Olorunfemi Yasiru Alimi. 2019. Political Instability and Migrants’ Remittances into Sub-Saharan Africa Region. GeoJournal 84 (6): 1657-75.

Aydas, Osman Tuncay, Kivilcim Metin-Ozcan, and Bilin Neyapti. 2005. Determinants of Workers’ Remittances: The Case of Turkey. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 41 (3): 53-69.

Bank of Mexico. 2025. (CA11) – Workers´ Remittances. Accessed October 27, 2025. Available online.

Bio, Demian. 2025. Remittances to Mexico Drop for Fourth Straight Month with Trump Policies Impacting Flux. The Latin Times, September 2, 2025. Available online.

European Union Global Diaspora Facility (EU-DiF). 2020. Youth-Focused Diaspora Engagement Initiatives. Brussels: EU-DiF. Available online.

Gamlen, Alan. 2006. Diaspora Engagement Policies: What Are They, and What Kinds of States Use Them? Centre on Migration, Policy and Society working paper No. 32, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK. Available online.

International Organization for Migration (IOM). N.d. Program 3×1 for Migrants. Accessed October 5, 2025. Available online.

Martinescu, Andra-Lucia. 2025. Diaspora Engagement Mapping: Malawi. Brussels: EU-DiF. Available online.

Rabat Process: Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development. 2020. Collection of Diaspora Engagement Practices. Brussels: Rabat Process: Euro-African Dialogue on Migration and Development. Available online.

Raji, Zainab. 2024. Harnessing the Potential of Remittances. Stanford Social Innovation Review, June 6, 2024. Available online.

Ratha, Dilip, Sonia Plaza, and Eung Ju Kim. 2024. In 2024, Remittance Flows to Low- and Middle-Income Countries Are Expected to Reach $685 Billion, Larger than FDI and ODA Combined. World Bank blog post, December 18, 2024. Available online.

René, Maldonado and Jeremy Harris. 2024. Remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean in 2024: Diminishing Rates of Growth. Washington, DC: Inter-American Development Bank (IADB). Available online.

Ruiz Soto, Ariel G. et al. 2021. Charting a New Regional Course of Action: The Complex Motivations and Costs of Central American Migration. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute (MPI) and World Food Programme. Available online.

Schöfberger, Irene and Marina Manke. 2023. Diasporas and Their Contributions: A Snapshot of the Available Evidence. International Organization for Migration (IOM) Global Data Institute thematic brief 3, July 2023, Berlin. Available online.

Sen, Ronojoy. 2021. Diaspora Engagement Mapping: Nepal. Brussels: EU-DiF. Available online.

Vezzoli, Simona and Thomas Lacroix. 2020. Building Bonds for Migration and Development: Diaspora Engagement Policies of Ghana, India and Serbia. Eschborn, Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ). Available online.

Wagner, James. 2025. Deportation Fears Are Fueling Money Transfers to Latin America. The New York Times, September 8, 2025. Available online.

Wasserman, Daniel Frederick. 2025. Using IEEPA to Limit Personal Remittances. Harvard Law Review, April 15, 2025. Available online.