This post was originally published on this site

On Shifting Sands in Africa’s Sahel Region: Tensions between Security and Free Movement

Women at a site for displaced people in Niger. (Photo: IOM/Aïssatou Sy)

Migration has long been a defining feature of Africa’s Sahel region, where historical trade routes, seasonal labor mobility, and transnational kinship networks have shaped patterns of movement. Today, the Sahel functions as a region both of origin and of transit, with significant intra-regional movement alongside growing northward migration towards North Africa and Europe.

However, the management of migration in the Sahel has undergone profound shifts in recent years, due to a combination of security concerns, economic pressures, environmental challenges, and external interventions. Coups in countries including Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have prompted international concern and led to a change in their posture towards migration management, among other issues. These three countries this year formally left the regional Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), a now 12-member organization which has sought to promote free-movement policies; the trio has formed the new Alliance of Sahel States. Their geopolitical withdrawal along with regional violent extremism, transnational crime, and other security challenges have led to increased border controls and restrictions on movement across the region.

At the same time, international actors—particularly the European Union—have played a large role in shaping migration policies in the region, through externalized border management strategies aimed at curbing irregular migration towards Europe. But the European Union’s impact has been mixed: While it has provided billions of euros to support regional migration management and other systems in the Sahel, the European Union has also provoked a backlash with its efforts. For example, after Niger’s 2023 coup, military authorities revoked a domestically unpopular 2015 anti-smuggling law that had been supported by Europe to halt irregular migration.

Intra-regional mobility within the Sahel remains vital for economic growth, social cohesion, and political stability. Yet the region’s migration management approach is now conflicted, torn between economic demands for openness (which often come from regional leaders) and security concerns pushing rigid borders (many of which come from Europe). This article examines the Sahel’s evolving migration governance.Haut du formulaire

Regional Mobility and Northward Migration Trends

Migration in the Sahel follows two major patterns: mobility within the region and northward migration towards North Africa and Europe. These two trends are shaped by a range of economic, political, and environmental factors, often overlapping as migrants shift approaches when opportunities arise or conditions change.

Intra-Regional Mobility

Historically, mobility within the Sahel has been a central part of economic and social life, with seasonal labor migration providing a livelihood strategy for millions. ECOWAS formalized this practice beginning in 1979 through its Protocol on Free Movement, which allows citizens of Member States to travel, reside, and work freely within the region. However, while this framework exists on paper (with several supplementary protocols following the initial 1979 one), implementation has faced numerous challenges due to security concerns, political instability, and pressure from external voices, particularly in Europe.

For instance, Côte d’Ivoire and Senegal have historically been major destinations for workers from Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, who often seek out labor-intensive sectors such as agriculture, mining, and construction. In Côte d’Ivoire, Burkinabe and Malian migrants have played a crucial role in the country’s cocoa and coffee industries for decades. However, following the Ivorian civil war (2002-11), these migrants often faced discrimination and expulsion. More recently, insecurity in Burkina Faso and Mali has pushed many migrants to move southward, to other coastal West African states, altering traditional migration patterns.

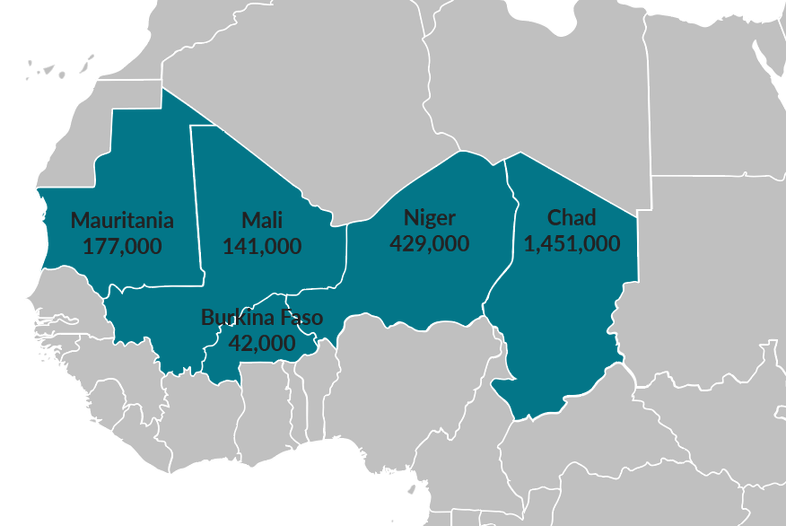

While economic-driven migration remains strong, conflict and insecurity—at times compounded by environmental degradation—have increasingly become primary drivers of forced displacement in the region. Jihadist violence has led to mass displacement in Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger, with millions of people forced to flee their homes. More than 2 million people in Burkina Faso were internally displaced as of June 2025. This displacement has triggered secondary international migration, as many internally displaced persons (IDPs) have crossed into neighboring countries. More than 2.2 million refugees and asylum seekers were living across the region in August 2025; tighter border controls and security measures have often limited their ability to move freely (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Refugees and Asylum Seekers in Select Sahel Countries Hosting Humanitarian Migrants, 2025

Notes: There is no single definition of which countries comprise the Sahel. The countries shown in this figure are among those commonly categorized as being Sahelian and which host large numbers of forcibly displaced people. Map is an illustration and is not intended to imply endorsement or acceptance of territorial boundaries.

Source: UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), “R4Sahel: Coordination Platform for Forced Displacements in Sahel,” updated August 3, 2025, available online.

Migration towards the Mediterranean

The other major migration trend involves northward movement towards North Africa and, ultimately, Europe. Traditionally, northbound migration has been driven by economic opportunities, with many Sahelian migrants working in Libya and Algeria in sectors such as construction, agriculture, and domestic work. Libya was for many years a major labor destination, with migrants from Chad, Mali, Niger, and Sudan making up a significant portion of the country’s workforce. The 2011 fall of Muammar Gaddafi and the subsequent civil war transformed Libya from a migrant destination into a dangerous transit zone. The fragmentation of Libya’s political landscape, the rise of militia groups, and EU-backed interception policies have made migration through the country increasingly perilous, with reports of human-rights abuses including detention, forced labor, and slavery-like conditions. Algeria has also taken a hardline stance on migration, periodically expelling thousands of Sahelian migrants—particularly Burkinabes, Malians, and Nigeriens—and leaving them stranded in the desert without food or water.

The situation is further complicated by bilateral agreements some North African countries have with European countries to externalize migration control. In response to European financial and political support, North African states have cracked down on irregular migration, increasing arrests and deportations and militarizing their borders. These measures have made some migration more dangerous, pushing individuals to take riskier paths through the Sahara, where many perish due to extreme conditions and lack of access to aid. The number of people who die in the Sahara is believed to be at least double those who perish in the Mediterranean Sea, which is often described as the world’s deadliest crossing, but because of the remoteness of the desert there are no exact figures.

At the same time, programs aimed at promoting voluntary return and reintegration have had limited success, as many returnees face economic hardship and social stigma. In Niger, for instance, returnees often struggle to reintegrate due to a lack of job opportunities, pushing some to attempt the journey again despite the risks.

Despite these challenges, factors including difficult economic and political conditions in origin countries make migration towards Europe seem attractive to many Sahelians. Nearly 22,000 nationals of Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger sought asylum in the European Union in 2024, the most in at least a decade. These dynamics illustrate the broader tensions in the Sahel’s migration patterns. While regional agreements theoretically facilitate intra-regional mobility, security concerns and international pressures have led to increasing restrictions. Meanwhile, migration to North Africa and Europe has continued despite heightened risks, demonstrating that restrictive border policies do not necessarily stop migration but rather reshape its routes in ways that make it more dangerous.

Evolving Migration Governance Frameworks

The system for governing this movement is a complex interplay of national policies, regional agreements, and international interventions, each shaped by shifting political, security, and economic realities. Historically, migration in the region was governed by a combination of informal cross-border arrangements and formal agreements such as the ECOWAS Protocol on Free Movement. This framework was rooted in the economic and cultural interconnectedness of regional countries, where seasonal migration and trade networks have long facilitated labor mobility and economic exchange. The African Union’s 2018-30 Migration Policy Framework for Africa similarly emphasizes the benefits of legal migration and calls for policies that facilitate labor mobility while protecting migrants. However, in recent years, this open-border model has come under increasing strain due to security concerns, leading to restrictive national policies that often contradict regional commitments to free movement.

One of the most visible shifts has been the securitization of mobility, driven largely by concerns about terrorism, organized crime, and irregular migration to Europe. Jihadist insurgencies led Sahel governments to tighten border controls, increasing surveillance and military operations in key transit areas. For instance, Niger was once a key transit hub for West African migrants heading towards Libya and Algeria but then implemented restrictive migration policies under EU pressure. Its 2015 anti-smuggling law criminalized the transport of migrants across the country, leading to the arrest of local smugglers and a significant decline in migration through Agadez, a major Nigerien gateway to the Sahara. While these measures reduced the visibility of migration, they also pushed migrants into more dangerous, informal paths, increasing the risks for individuals and strengthening criminal networks specializing in smuggling and trafficking. They also helped spur domestic opposition, since the Agadez economy partly depended on migration-related activities. The law was revoked shortly after a military junta toppled President Mohamed Bazoum in 2023.

As such, implementation of AU and ECOWAS free-movement frameworks remains uneven, as governments typically prioritize security over integration. This tension is evident in Mali, where migration policies have oscillated between adherence to free-movement principles and restrictive border measures that respond to security threats. The country’s ongoing political instability has further complicated efforts to establish a coherent migration framework that balances security, economic, and humanitarian considerations.

Evolving approaches thus reflect a struggle between regional integration and security imperatives. The implementation of policies promoting free movement has been undermined by external and domestic pressures. This situation highlights the challenges of reconciling migration governance with broader development and security strategies in a region where mobility is both an economic necessity and a source of geopolitical tension.

Impact of External and Regional Actors

The Sahel’s migration governance is profoundly shaped by the interventions of extracontinental and regional actors, whose policies often reflect competing priorities.

The European Union has shaped migration policies through its financial and technical support, which often ties aid and development assistance to stricter border controls. The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF), established in 2015, resulted in 2.2 billion euros for the Sahel and its Lake Chad area, with the goal of addressing what policymakers have identified as the root causes of migration and strengthening border security. Of this, 366 million euros was for border management, migration control, and reintegration programming. EUTF funding for new programs ended in 2021, but ongoing support will continue through 2025. While these initiatives may at times have contributed to migrant safety, they have also reinforced a security-focused approach that has prioritized border enforcement. It is also unclear if they were ultimately effective: “There is still insufficient data to demonstrate how sustainably the EUTF is addressing the root causes of irregular migration and forced displacements,” the European Court of Auditors said in a mid-2024 examination. Meanwhile, the externalization of migration controls to Sahelian states effectively transformed them into buffer zones, where migration was contained before reaching Europe, often at great human cost.

Libya has become one of the most glaring examples of the consequences of EU-driven migration policies. Following the 2011 collapse of the Gaddafi regime, Libya descended into chaos. The European Union and its Members States have supported the Libyan Coast Guard’s ability to intercept boats in the Mediterranean, resulting in thousands of migrants being forcibly returned to Libya, where they face arbitrary detention, extortion, and horrific abuse. Similar—if less extreme—dynamics have emerged in the Sahel, where external funding has incentivized restrictive migration policies.

Countervailing Pressure from within Africa

Meanwhile, regional African organizations’ liberalizing influence has been more constrained, often struggling to counterbalance the dominance of European policies and funding. And while Mali and Burkina Faso had remained committed to regional integration, their internal security crises have led to increased border restrictions, limiting the effectiveness of regional policies

While the African Union has sought to present a more development-oriented vision of migration with frameworks emphasizing the benefits of legal movement, implementation remains weak due to limited political will and pressures for migration control. The bloc’s inability to enforce its migration policies reflects a broader challenge in African regional governance, wherein continental frameworks are often unable to counteract external pressures.

The influence of the African Union and ECOWAS remains limited when faced with European migration policies—and funding—that prioritize containment. On the other hand, the recent move by Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger to withdraw from ECOWAS in the face of pressure to restore democratic rule underscores the bloc’s complicated regional position.

A more balanced migration governance approach in the Sahel would require a shift away from short-term security solutions towards inclusion of policies that recognize the role of migration in regional development. This would involve strengthening regional institutions, ensuring that migration policies align with economic and labor needs, and addressing drivers of forced displacement.

The competing agendas of local, regional, and external actors result in a fragmented migration policy landscape in the Sahel. While the European Union’s security-driven approach has dominated migration management in recent years, it has failed to provide sustainable solutions that balance control with development and rights-based considerations. Regional policymakers remain constrained by political and financial dependencies on external partners. And meanwhile national leaders have seemed torn between promises of development and fears of insecurity. The future will depend on the degree of autonomy that regional institutions have to shape policies that reflect regional realities of mobility, rather than simply responding to external pressures.

While restrictions have achieved some success in reducing irregular migration, they have also had serious unintended consequences, such as pushing migrants into more dangerous and exploitative routes and contributing to widespread human-rights abuses, particularly in transit countries such as Libya.

On the other hand, regional organizations continue to advocate for free movement, emphasizing the economic and social benefits of mobility. Yet the internal unrest and military control of countries such as Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger have undercut regional integration frameworks. Moreover, the African Union’s ambitious vision of a continent-wide free-movement agreement faces significant challenges beyond the Sahel or West Africa.

The challenge, therefore, is to find a balance between addressing some of the region’s key drivers of migration—such as conflict, economic instability, and environmental degradation—and ensuring that migration policies do not inadvertently increase vulnerabilities or limit opportunities for those who choose to migrate. A more effective and sustainable migration governance model would likely involve a shift towards a more comprehensive approach that prioritizes both security and human rights, involving greater focus on the underlying drivers of migration while also protecting individuals’ rights. Regional institutions would likely play a more assertive role in shaping these kinds of migration policies, supported by a more equitable partnership with external actors, one that recognized the long-term benefits of mobility for regional development and integration. A balanced, rights-based approach to migration in the Sahel would not only foster better governance in the region but also contribute to a more just and sustainable global migration framework.

Sources

Adepoju, Aderanti, Alistair Boulton, and Mariah Levin. 2010. Promoting Integration through Mobility: Free Movement under ECOWAS. Refugee Survey Quarterly 29 (3): 120-44. Available online.

African Union. 2006. The Migration Policy Framework for Africa. Executive Council, Ninth Ordinary Session, Banjul, the Gambia, June 25-29, 2006. Available online.

Amnesty International. 2025. EU-Libya: EU’s Migration Cooperation with Libya Is ‘Morally Bankrupt’ and Amounts to Complicity in Violations. Press release, July 8, 2025. Available online.

DeAngelo, Michael. 2025. Counterterrorism Shortcomings in Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. Foreign Policy Research Institute, March 3, 2025. Available online.

Elbagir, Nima, Raja Razek, Alex Platt, and Bryony Jones. 2017. People for Sale: Where Lives Are Auctioned for $400. CNN, November 15, 2017. Available online.

European Court of Auditors. 2024. Special Report 17/2024: The EU Trust Fund for Africa: Despite New Approaches, Support Remained Unfocused. Luxembourg: European Court of Auditors. Available online.

European Union. 2023. Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Updated December 2023. Available online.

Global Centre for the Responsibility to Protect. 2025. Central Sahel (Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger). Updated July 15, 2025. Available online.

Golovko, Ekaterina and Laurens Willeme. 2024. Niger’s Repeal of the 2015/36 Anti-Smuggling Law. Wassenaar, the Netherlands: Clingendael Institute. Available online.

Human Rights Watch (HRW). 2019. No Escape from Hell: EU Policies Contribute to Abuse of Migrants in Libya. New York: HRW. Available online.

Bas du formulaireNeumann, Kathleen and Frans Hermans. 2017. What Drives Human Migration in Sahelian Countries? A Meta‐Analysis. Population, Space and Place 23 (1): e1962. Available online.

Stille, Sophia. 2023. The Criminalization of Mobility in Niger: The Case of Law 2015-36. ASILE Global Portal blog post, November 2023. Available online.

Strik, Tineke and Erik Marquardt. 2023. Parliamentary Question – P-001069/2023: EU Support to the Libyan Coast Guard in the Light of the UN Conclusions and Recent Incidents. European Parliament, March 29, 2023. Available online.

UN Hıgh Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). 2025. R4Sahel: Coordination Platform for Forced Displacements in Sahel. Updated August 3, 2025. Available online.

Yaro, D. S. 2019. Causes of the 2002-1011 Ivorian Political Armed Conflict and Its Ramification on Education. UDS International Journal of Development 6 (3): 185-200. Available online.