This post was originally published on this site

Canada’s Long-Standing Openness to Immigration Comes Under Pressure

Canadians welcome Syrian refugees to Toronto. (Photo: stacey_newman/iStock.com)

Canada is recognized as a global leader in immigration policy. Unlike countries where immigration is a polarizing issue, in Canada it has historically generally been viewed as part of the national narrative and essential to economic growth. However, in recent years public debate has intensified, amid a rapid increase in the admission of permanent residents, temporary workers, and international students. There has been growing concern about whether Canada’s housing supply, infrastructure, and health services can keep pace with this growth. Nearly 60 percent of Canadians polled in late 2024 indicated the country was accepting too many newcomers—the first time since 2000 that most respondents believed immigration levels were too high. Nonetheless, a majority in that 2024 poll also expressed the view that immigration was beneficial for Canada.

While most countries restricted immigration during the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada rapidly expanded admissions for economic recovery. Targets for permanent residents rose from 341,000 in 2019 to 437,000 in 2022, with a goal of admitting 500,000 annually by 2025. Amid mounting public pressure, however, the government backtracked and lowered targets in 2024. It also announced plans to reduce the number of temporary residents.

Still, immigration remains crucial for Canada’s economy. With the country’s aging population and low birth rates, immigrants have been the primary drivers of both labor-force and overall population growth since the 1990s. As of 2021, nearly 8.4 million foreign-born individuals made up 23 percent of Canada’s population. In 2023, immigrants accounted for 28.9 percent of the national labor force.

This country profile provides an overview of Canada’s immigration history and recent policies. The article offers information on major immigration pathways, rising temporary immigration in the 21st century, and the role of immigration in Canadian society.

Current Immigrant Population in Brief

Canada has a proactive and managed immigration system designed to meet economic, demographic, and humanitarian objectives via three main pathways. The economic stream, which is the largest, includes the Express Entry process for selecting skilled workers through a points-based system as well as the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) to address regional labor shortages. The family reunification stream allows Canadian citizens and permanent residents to sponsor relatives. And the humanitarian stream includes the refugee resettlement and asylum programs.

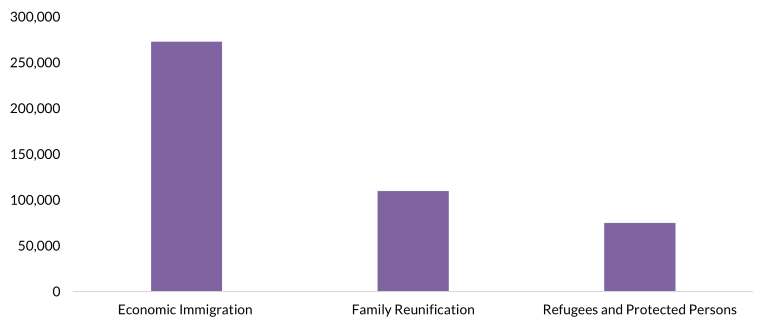

Figure 1. New Permanent Resident Admissions to Canada, by Category, 2023

Source: Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), 2024 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration (Ottawa: IRCC, 2024), available online.

Immigrants’ origins have shifted significantly over the last five decades. Once dominated by Europeans, most newcomers now arrive from Asia, particularly India (the origin of 10.7 percent of foreign-born residents in 2021) and China and the Philippines (8.6 percent each). Immigration from Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America has also grown in the past two decades.

Figure 2. Immigrant Population of Canada, by Region of Birth, 2021

Source: Statistics Canada, “Immigrant Population by Selected Places of Birth, Admission Category, and Period of Immigration, 2021 Census,” October 26, 2022, available online.

Historical Immigration Policy Evolution

A settler colonial state, Canada has a long history of exclusionary immigration policies—even though colonial settlers themselves were immigrants whose arrival and settlement were premised on the displacement of Indigenous peoples. For example, the 1885 and 1923 iterations of the Chinese Immigration Act introduced a head tax and later imposed near-total exclusion of Chinese immigrants. Japanese immigration was similarly limited through the 1907 “Gentlemen’s Agreement” with Japan, under which the Japanese government agreed to restrict emigration to Canada to 400 male laborers per year. (Canada’s neighbor, the United States, had similar limitations on Chinese and Japanese immigration during the same period.) In 1908, Canada’s Continuous Journey Regulation effectively blocked immigration from India, by requiring arrivals to come via a direct route—a condition that was virtually impossible to meet. A 1911 order-in-council explicitly barred Black immigrants, and severe restrictions were placed on Jewish refugees throughout the early to mid-20th century.

In 1962, driven by the need to grow the economy and respond to labor-market demands, the government replaced country- and race-based selection of immigrants with a skill-based model. This shift culminated in the 1967 introduction of the points system, which assessed applicants on education, language, work experience, and age. That same year, the Immigration Appeal Board was established and Canada expanded its refugee program to claimants from outside Europe.

It was during this period, notably in 1971, that Canada adopted multiculturalism as an official policy, recognizing cultural and religious diversity as an essential element of Canadian identity. In 1982, multiculturalism was recognized in Section 27 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act was enacted in 1988. The act promotes the idea that all Canadians should have the opportunity to preserve, enhance, and share their cultural heritage at both the individual and community level.

The 1976 Immigration Act set formal objectives for immigration policy, prioritized refugee resettlement, and introduced private sponsorship—an innovation that later became a global model. In 1986, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) awarded the people of Canada the Nansen Medal for their efforts to welcome Indochinese refugees. The Supreme Court’s 1985 Singh v. Canada decision affirmed the rights of refugee claimants (also known as asylum seekers) to an oral hearing under the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, leading to the creation of the Immigration and Refugee Board in 1989. The 2002 Immigration and Refugee Protection Act replaced the 1976 law, consolidating existing immigration laws and formalizing Canada’s refugee determination process.

Policy Landscape in the 21st Century

Since the early 2000s, Canada’s immigration system has seen a surge in temporary work permit holders, rising international student numbers, and the expansion of two-step migration pathways allowing some temporary residents to transition to permanent status. Express Entry, launched in 2015, reshaped skilled immigrant selection, giving greater priority to newcomers with ties to employers. Most recently, policies have shifted toward greater restriction.

Changes to Temporary Foreign Worker Programs

Initially designed for agriculture and caregiving, the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP), established in 1973, traces its roots to earlier programs including the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (1966). Over time, the TFWP expanded to include both low- and high-wage streams across various industries.

Concerns about worker exploitation and labor-market displacement led to major reforms in the 2000s, including caps on low-wage foreign workers, higher employer fees, and stricter enforcement. These changes significantly reduced the use of TFWP in sectors such as food services and retail.

To better manage labor needs, the government split temporary migration into two streams: the TFWP, which requires a Labor Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) to demonstrate that hiring a foreign worker will not negatively affect Canadian workers, and the International Mobility Program (IMP), which does not. The IMP includes diverse work permit categories, including postgraduation work permits for international students, working holiday visas, permits for workers covered by mobility provisions of international trade agreements (such as the free trade agreement between Canada, Mexico, and the United States, as well as the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement with the European Union), permits for refugee claimants, and work permits for the spouses of skilled workers and students. Though often associated with high-skilled professionals, many IMP permits go to low-wage workers who face limited pathways to permanent residency and precarious employment. The absence of LMIA requirements has raised concerns about labor protections and impacts on domestic workers.

While TFWP numbers have declined, the IMP has expanded rapidly over the years, driven by growing numbers of international student graduates, refugee claimants, and employers seeking LMIA-exempt options for hiring workers.

Growth of the International Student Program

Between 2000 and 2023, Canada’s international student population grew eightfold, driven in large part by Ontario public community colleges—particularly their partnerships with private career colleges focused on vocational training. Promoted by the government as ideal immigrants due to their domestic education, language skills, and Canadian work experience, international students became central to immigration policy. Facing declining domestic enrollment and reduced public funding, institutions have also increasingly relied on international students, whose tuitions were on average more than five times higher than Canadians’ as of 2023. Canada also attracted students diverted by more restrictive immigration policies in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia—the three other major countries in the international education sector.

International students have supplied key labor in sectors including food service, retail, and health care, as they are allowed to take up part-time employment during their studies. In 2022, Canada lifted a 20-hour weekly work limit for international students to address labor shortages; the limit was reinstated, at 24 hours per week, in 2024, amid public pressure over rising student numbers.

The 2008 introduction of the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program under the IMP allowed international graduates to apply for up to three years of open work permits, replacing earlier rules that gave them only 60 days to secure a job within their field. Since 2000, roughly 30 percent of international students overall (and 50 percent of four-year university graduates) have gained permanent residence within a decade of arrival, often leveraging this work experience. Yet concerns have arisen about increasing low-quality jobs, labor-market pressure, and rising housing demand.

Figure 3. Temporary Immigrants in Canada, by Pathway, 2000-23

Notes: Figure shows the temporary immigrant population as of December 31 of the given year. Figure does not include asylum seekers and other protected groups.

Source: IRCC, “Temporary Residents: Study Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Study Permit Holders on December 31st by Country of Citizenship,” updated May 18, 2024, available online; IRCC, “Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates,” updated May 5, 2025, available online.

The expansion of the IMP and international student program led to a non-permanent resident population that has significantly exceeded the number of new permanent immigrants admitted annually (see Figure 4).

Figure 4. Annual New Admissions of Permanent Residents and Total Population of Non-Permanent Residents, 2015-24

Notes: Data for new permanent resident admissions show annual arrivals, also known as flow. The non-permanent resident data refer to the resident population (also known as stock), not annual new arrivals, and may include status changes rather than new entries. The figure shows the temporary immigrant population as of December 31 of each year, except for 2024, which reflects the population as of October 1. It does not include asylum seekers or other protected groups, such as refugees, persons in need of protection, and individuals admitted under special humanitarian measures (including for Afghan and Ukrainian nationals).

Sources: IRCC, “Temporary Residents: Study Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Study Permit Holders on December 31st by Country of Citizenship;” IRCC, “Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates;” Statistics Canada, “Estimates of the number of Non-Permanent Residents by Type, Quarterly,” updated March 19, 2025, available online; IRCC, “Permanent Residents – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Permanent Residents by Province/Territory and Immigration Category,” updated March 31, 2025, available online.

Evolution of Permanent Economic Immigration

In the 2010s, Canada’s permanent immigration system shifted from a first-come, first-served model to a hybrid framework that combined human-capital factors (such as education, language proficiency, work experience, and age) with demand-driven criteria (such as Canadian experience, individuals’ job offers, and regional labor needs). The Federal Skilled Worker Program (FSWP) originally emphasized only human capital but often produced labor-market mismatches due to new permanent residents’ skills not being totally aligned with employer needs. Reforms introduced educational credential verification and encouraged two-step migration, with many immigrants first gaining Canadian education or work experience before applying for permanent residence.

Two new streams—the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP) and the Canadian Experience Class (CEC)—surpassed the FSWP in size by the mid-2010s. The PNP, created in 1998, allows provinces to nominate candidates based on local labor needs; the CEC, created in 2008, targets skilled temporary foreign workers and international students with at least one year of Canadian experience. The PNP stream also relaxed some federal requirements on language, education, and occupational skill level, broadening access to permanent residency. While it has supported immigration to smaller communities, retention rates have varied, with Atlantic Canada (New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island) historically struggling to retain nominees.

Quebec operates an independent selection system under the Canada–Quebec Accord, prioritizing French-speaking immigrants through programs such as the Quebec Skilled Worker Program and the Quebec Experience Program.

The 2015 introduction of Express Entry further transformed economic immigration. Express Entry replaced the queue-based system with the Comprehensive Ranking System, which ranks candidates based both on human capital and factors including Canadian experience, job offers, and provincial nominations.

Express Entry also introduced a two-stage process: Candidates submit an expression of interest, enter a ranked pool if eligible, and receive invitations to apply for permanent residence based on biweekly draws. While this model improved efficiency, it also introduced uncertainty as every draw is competitive, depending on who is in the pool at that particular moment. Those with the highest scores are then invited to apply for permanent residency.

In 2023, Express Entry was expanded to include category-based selection, prioritizing candidates with work experience in high-demand sectors such as health care; the science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields; trades; and transportation. While this targeted approach addresses immediate shortages, critics have warned it may shift selection criteria at the expense of broader human capital and expected adaptability.

Recent Shifts in Economic Immigration Policy

After a period of rapid growth post-pandemic, Canada adopted a more restrictive immigration approach in 2024, amid public concerns about housing shortages, labor-market pressures, and integrity issues in the international student system.

In January 2024, the federal government capped international study permits at 360,000 and introduced stricter eligibility rules, resulting in a 45 percent drop in approvals. In August, pre-pandemic restrictions were reinstated in the TFWP, including tighter hiring caps and shorter permit durations. For the first time, Canada also set a target of reducing the temporary resident population, from 6.5 percent of all residents to 5 percent by 2026. Permanent immigration targets were likewise scaled back—from 500,000 to 365,000 annually by 2027—and PNP allocations were halved from around 110,000 to 55,000 per year. In November 2024, Ottawa placed new limits on postgraduation work permits, narrowing students’ pathways to permanent residency. In December, Express Entry was revised to remove points for arranged job offers; reduce fraud; and refocus on education, language, and Canadian experience, restoring it closer to a human capital-based system.

Figure 5. Canada’s Annual Immigration Targets, 2000-27

Sources: Statistics Canada, “Estimates of the Components of International Migration, Quarterly,” updated March 19, 2025, available online; IRCC, “Government of Canada Reduces Immigration,” press release, October 24, 2024, available online.

While more than 40 percent of new permanent residents are expected to come from temporary streams, the shrinking number of permanent residency spots has raised doubts about the system’s capacity to absorb those who are eligible. A crucial question is what will happen to those whose permits expire: Will they return home or fall out of legal status and potentially face removal? These unresolved issues carry significant implications for immigration policy and public trust going forward.

Recent policy shifts signal a move toward a more limited and regulated system. While intended to address public concerns and restore integrity, the consequences are far-reaching. Postsecondary institutions face financial strain, Canada’s reputation as a destination for international students has come under scrutiny, and employers in key sectors face deepening labor shortages. Meanwhile, the reduction in permanent residency spots has left many applicants effectively settled in the country for several years, in prolonged precarity, with fewer viable paths to permanence.

Family Reunification Policies

Most permanent immigrants and many temporary residents arrive with family members. However, temporary workers in the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program (SAWP)—mostly men from the Caribbean and Mexico—are prohibited from bringing family members, often resulting in prolonged and repeated separation. This restriction stands in stark contrast to other temporary migration streams. Until 2025, spouses of most temporary foreign workers and students were eligible for open work permits. In January 2025, eligibility was narrowed; now, only spouses of high-skilled workers in select sectors and students in master’s, doctoral, or designated professional programs qualify. Dependent children of temporary workers and international students are largely ineligible to work legally.

Meanwhile, those seeking to join family already in Canada must apply through the Family Class Sponsorship Program, which supports both family formation and reunification. Despite its significance, this stream accounts for less than 30 percent of permanent resident admissions and faces significant backlogs. In 2023, processing times for spousal sponsorship were reduced and access to open work permits expanded for in-Canada applicants awaiting decisions. Still, couples seeking reunification could endure wait times up to 24 months as of this year.

Similarly, the Parents and Grandparents Program has struggled with caps, backlogs, and delays. This program has since moved to a randomized intake system with annual quotas, but demand continues to far outpace supply, raising concerns over fairness and accessibility. To expand options for bringing in parents and grandparents, the government introduced the Super Visa in 2011, offering holders multiple entries and stays of up to two years at a time, for a total duration of up to ten years, without conferring permanent residence.

Humanitarian Immigration

Less than 20 percent of permanent immigrants to Canada arrive as humanitarian migrants. Canada’s protection system consists of two main programs: the Refugee and Humanitarian Resettlement Program, which assists individuals seeking protection from abroad, and the In-Canada Asylum Program, which processes claims made at ports of entry or from within the country. Within the resettlement stream, refugees are admitted as permanent residents through three main programs: Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR), Private Sponsorship of Refugees (PSR), and Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR). In recent years, a slight majority have come through the PSR program (see Figure 6).

Canada was the first country to introduce a private sponsorship program, in 1979, in which citizens and community groups assist refugee arrivals in integrating into their new communities. Since then, tens of thousands of refugees have been resettled through sponsors’ efforts. However, persistent demand by sponsor groups, inadequate allocations in the annual levels plans, and processing delays have led to significant backlogs of refugee applications through this stream.

The GAR program resettles refugees referred by UNHCR or other partners, prioritizing those with urgent protection needs. These refugees receive temporary shelter and one year of financial support from the federal government (privately sponsored refugees receive this support from their sponsors). As the name suggests, the BVOR program involves features of both other programs, involving support from sponsors and the government alike. No matter how they arrive, refugees have free access to services such as language training, education, health care, and employment assistance.

Figure 6. Resettled Refugee Admissions to Canada, by Program, 2016-22

Source: IRCC Evaluation Division, Evaluation of the Refugee Resettlement Program (Ottawa: IRCC, 2024), available online.

In the past decade, Canada has launched several major resettlement initiatives, bringing in approximately 100,000 Syrian refugees since 2015, as well as Iraqi, Rohingya, and Congolese refugees. Between 2021 and 2024, more than 55,000 Afghans were resettled through various programs, many under GAR. Resettled refugees’ top countries of origin have shifted over time in response to changing global displacement patterns (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Top Countries of Origin for Resettled Refugees in Canada, by Program, 2015-24

Source: IRCC, “Resettled Refugees – Monthly IRCC Updates,” updated March 31, 2025, available online.

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, Canada launched the Canada-Ukraine Authorization for Emergency Travel (CUAET), a temporary program offering Ukrainians access to work, study, and settlement services outside the refugee system. While more than 960,000 applications were approved, only about 300,000 individuals arrived before the March 31, 2024 deadline, after which no further entries were allowed. The program was praised for its speed and coordination but led to criticism for illustrating how other crises, such as Afghanistan’s, have been met with slower, more limited responses. Concerns have also been raised about the temporary nature and uncertainty of status for CUAET holders with no clear pathway to permanent residence. Canada’s responses to conflicts in Sudan and Gaza have been relatively small and ad hoc and mostly limited to individuals with extended family in Canada.

Despite rising global need and a pause in U.S. refugee admissions under the Trump administration, Canada’s 2025-27 Immigration Levels Plan lowered overall resettlement targets and shifted emphasis toward private rather than government sponsorship.

Evolving Relations between Canada and the United States

The Canada-U.S. border, which is the longest in the world, is crossed daily by approximately 400,000 people, including commuters, visitors, and individuals with family or social ties on both sides. It is not a heavily militarized or securitized boundary; rather, it typically unites the two countries through the routine movement of people and goods.

However, this openness has been complicated by evolving asylum policy and geopolitical dynamics. Under the Safe Third Country Agreement (STCA) implemented by the two governments in 2004, asylum seekers crossing the border must make their protection claim in the first country they reach: Canada or the United States. As a result, most claimants arriving at official land border crossings from the United States are turned back. However, because the STCA initially applied only to official ports of entry, many asylum seekers began entering through unofficial border crossings such as Roxham Road (a small road connecting New York and Quebec) and Emerson, Manitoba (across from Minnesota). Between 2017 and 2023, 95,600 individuals crossed at Roxham Road, including asylum seekers from around the world.

To manage rising claims, in 2022 the government allocated CAD 1.3 billion over five years for its asylum system. The following March, Canada and the United States jointly announced an expansion of the STCA to cover the entire land border, allowing Canada to close Roxham Road and return border crossers seeking protection, so long as they are detected within 14 days of arrival. However, Canadian legal experts have questioned whether the United States still qualifies as a safe third country, citing recent U.S. policy changes that restrict access to asylum as well as rapid deportations with limited due process and U.S. government narratives that villainize unauthorized migrants. Meranwhile, as the United States has adopted a more muscular enforcement policy and revoked temporary protections for various groups, analysts have prepared for an uptick in crossings into Canada.

In late 2024, ahead of looming U.S. tariffs, Canada launched a border surveillance initiative, Project Disrupt and Deter, which involves drones and helicopters monitoring the border. While framed as a strategy to combat cross-border smuggling of drugs and weapons, this shift has raised concerns about the securitization of what has long been a largely open and cooperative border.

Labor-Market Integration and Economic Outcomes

Despite often arriving in Canada with strong educational qualifications, many immigrants face significant and persistent employment disparities relative to the Canadian born. While both men and women encounter barriers, women of minority ethnic backgrounds are particularly disadvantaged. Newcomers have long experienced challenges in the labor market; however, prior to the 1980s, these disadvantages typically diminished over time. Long-term immigrants—those residing in Canada for a decade or more—often caught up to or even surpassed the earnings of their Canadian-born counterparts. Since the late 1980s, however, this trend has reversed, with long-term immigrants experiencing enduring earnings gaps that no longer close over time.

Several factors contribute to these disparities. On the supply side, limited language proficiency or perceived communication barriers often hinder access to skills-appropriate employment. Many immigrants also lack social and cultural capital such as local networks and familiarity with workplace norms. On the demand side, unconscious bias and devaluation of foreign credentials and experience disadvantage newcomers. Non-European immigrants in particular have faced systemic barriers, including employer skepticism of foreign qualifications. The widespread requirement for Canadian work experience can act as a structural barrier, often diverting newcomers into low-wage “survival jobs” that underutilize their skills and erode professional networks and confidence. More broadly, a disconnect between immigration selection criteria and actual labor-market needs has left many highly qualified immigrants struggling to secure stable, well-matched employment.

These challenges have been compounded by structural changes in the labor market itself—most notably, the rise of precarious employment, the decline of unionized jobs, and the growth of low-wage service sectors. These shifts have disproportionately affected newcomers, whose entry into the labor market increasingly coincides with heightened job insecurity, limited upward mobility, and fewer opportunities for long-term career progression.

Policy Responses and Labor-Market Trends

All the same, in the past decade, policy reforms and labor-market trends have modestly improved immigrants’ average earnings. A key factor has been the growth of Canada’s two-step immigration system, which prioritizes candidates with prior Canadian work experience. This has facilitated better labor-market integration for some, especially immigrants previously employed in high-skilled, high-wage jobs. The 2015 launch of Express Entry reinforced this shift by awarding more points for Canadian work experience, language skills, and recognized foreign credentials.

Favorable economic conditions also contributed. From 2010 to 2019, the national unemployment rate dropped from 8.2 percent to 5.7 percent, stabilizing at 5.4 percent in 2023. Strong demand for skilled workers helped narrow some wage gaps, particularly for immigrant men with more than ten years’ residence in Canada. While long-term immigrant men saw modest earnings gains from 2010 to 2020, women—especially recent arrivals—still face sizable wage gaps (see Figure 8).

Figure 8. Weekly Earnings Disparities Between Immigrants and the Canadian Born (ages 25-54), by Gender and Duration of Residence, 2000-20

Notes: Recent Immigrants are foreign-born individuals who became permanent residents of Canada within the past ten years; Long-Term Immigrants are those who have been permanent residents for at least ten years.

Source: Feng Hou, The Improvement in the Labour Market Outcomes of Recent Immigrants since the Mid-2010s (Ottawa: Statistics Canada, 2024), available online.

Despite these improvements, major challenges remain, particularly around occupational skill mismatch. Data from 2016 showed that about 40 percent of immigrants, including those with university degrees, were employed in jobs below their skill level; by 2021, the overeducation rate among recent immigrants had declined to just under 27 percent. Recent immigrants are still far more likely than their Canadian-born counterparts to be overqualified for their jobs, and progress in improving skill utilization has been slow.

Citizenship and Social Integration

While challenges persist, most immigrants in Canada report a strong sense of belonging. This sentiment has traditionally been reflected in high naturalization rates, as permanent residents are eligible to apply for citizenship after three years and a relatively simple test. However, in recent years, the proportion of eligible immigrants who naturalize has declined markedly. In 1996, 75 percent of recent immigrants meeting the residency requirement became citizens; by 2021 this figure fell to just 46 percent.

The decline in naturalization rates among recent immigrants reflects a combination of policy, sociodemographic, and transnational factors. Policy changes introduced by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper in the early 2010s made citizenship more difficult to access. These included higher application fees, stricter language requirements, a more demanding citizenship exam, and reduced funding for citizenship preparation classes. These reforms created barriers, especially for immigrants with lower income, less education, and limited language proficiency. Although many of these measures were reversed by the Liberal government under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, naturalization rates have continued to fall, suggesting other dynamics are at play. Almost half the most recent decline occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic, when application processing delays and citizenship ceremony restrictions suppressed access. However, structural and transnational influences—such as growing economic opportunities and nationalist sentiments in some origin countries, and the absence of dual citizenship options in countries including China and India—also appear to be deterring uptake.

The drop has been particularly stark among East and Southeast Asian immigrants, with just 25 percent of eligible East Asian immigrants acquiring citizenship in 2021. This raises important questions about the inclusiveness and equity of Canada’s integration model.

Shifting Public Opinion on Immigration

Canadian public sentiment toward immigration remained largely positive throughout the 2000s and 2010s, according to the Environics Institute for Survey Research. As recently as 2022, more than two-thirds of Canadians disagreed with the statement, “Overall, there is too much immigration to Canada.”

However, public opinion has shifted sharply in the past few years. In 2024, 58 percent of Canadians believed immigration was too high—a 14-point increase from 2023 and the highest share since 1998. This shift, the fastest recorded since researchers began asking the question in 1977, appears to be driven by economic anxieties, housing shortages, and declining confidence in government management of immigration. Notably, these concerns are now evident across ethnic and generational lines, including among immigrants themselves. Although 68 percent of respondents in 2024 still said immigration was economically beneficial, support was higher in previous years. Concerns over integration have also grown, with 57 percent of Canadians saying they believed newcomers fail to adopt “Canadian values.” This points to a growing tension in public opinion between perceived economic contributions and concerns about cultural integration.

While all major political parties in Canada officially support immigration, polling suggests attitudes have diverged along partisan lines. According to the same survey, 80 percent of Conservative supporters believed immigration levels were too high, compared to 45 percent of Liberal supporters. Notably, the opinion that immigration levels were too high increased across the political spectrum.

A Nation at an Inflection Point

Canada’s immigration system is at a crossroads.

While immigration remains essential for addressing labor shortages and demographic needs, concerns over housing affordability and absorptive capacity must be addressed substantively to ensure continued public support. These pressures are unfolding amid a rapidly shifting global geopolitical environment, marked by rising humanitarian and economic displacement, protectionist trade policies, and increased competition for skilled workers.

In this climate, newly elected Prime Minister Mark Carney has adopted a stabilization strategy, continuing the Liberal plan to moderate immigration levels in response to capacity concerns. Unlike Conservative leader Pierre Poilievre, whom Carney defeated in the April 2025 election and whose rhetoric often frames immigration as a source of crisis, Carney presents newcomers as drivers of economic growth and demographic renewal. Immediately after the election, he emphasized the need to maintain lowered permanent resident admissions and cap temporary residents to ease pressure on housing, health care, and other public services.

As international migration patterns evolve, Canada’s ability to adapt—through policies that align economic needs with public expectations—will determine whether it remains a global leader in managed migration.

Sources

Banerjee, Rupa and Laura Lam. 2024. Paths to Permanence: Permit Categories and Earnings Trajectories of Workers in Canada’s International Mobility Program. Canadian Public Policy 50 (S1): 143-160. Available online.

Chishti, Muzaffar and Julia Gelatt. 2023. Roxham Road Meets a Dead End? U.S.-Canada Safe Third Country Agreement Is Revised. Migration Information Source, April 27, 2023. Available online.

Crossman, Eden, Youjin Choi, Yuqian Lu, and Feng Hou. 2022. International Students as a Source of Labour Supply: A Summary of Recent Trends. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online.

Crossman, Eden, Feng Hou, and Garnett Picot. 2020. Two-Step Immigration Selection: A Review of Benefits and Potential Challenges. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online.

Environics Institute for Survey Research. 2024. Canadian Public Opinion about Immigration and Refugees. Toronto: Environics Institute for Survey Research. Available online.

Hou, Feng. 2024. The Improvement in the Labour Market Outcomes of Recent Immigrants since the Mid-2010s. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online.

Hou, Feng and Garnett Picot. 2024. The Decline in the Citizenship Rate Among Recent Immigrants to Canada: Update to 2021. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). 2024. 2024 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration. Ottawa: IRCC. Available online.

—. 2024. Temporary Residents: Study Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Study Permit Holders on December 31st by Country of Citizenship. Updated May 18, 2024. Available online

—. 2025. Government of Canada Reduces Immigration. Press release, October 24, 2024. Available online.

—. 2025. Permanent Residents – Monthly IRCC Updates – Canada – Permanent Residents by Province/Territory and Immigration Category. Updated March 31, 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. Resettled Refugees – Monthly IRCC Updates. Updated March 31, 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. Temporary Residents: Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and International Mobility Program (IMP) Work Permit Holders – Monthly IRCC Updates. Updated May 5, 2025. Available online.

Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Evaluation Division. 2024. Evaluation of the Refugee Resettlement Program, Ottawa: IRCC. Available online.

Kelley, Ninette, Jeffrey G. Reitz, and Michael J. Trebilcock. 2025. Reshaping the Mosaic: Canadian Immigration Policy in the Twenty-first Century. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Pardy, Kandice. 2023. Why Are Some Refugees More Welcome in Canada than Others? Policy Options, February 27, 2023. Available online.

Schimmele, Christoph and Feng Hou. 2024. Trends in Education–Occupation Mismatch among Recent Immigrants with a Bachelor’s Degree or Higher, 2001 to 2021. Ottawa: Statistics Canada. Available online.

Statistics Canada. 2022. Immigrant Population by Selected Places of Birth, Admission Category, and Period of Immigration, 2021 Census. October 26, 2022. Available online.

—. 2025. Estimates of the Components of International Migration, Quarterly. Updated March 19, 2025. Available online.

—. 2025. Estimates of the Number of Non-Permanent Residents by Type, Quarterly. Updated March 19, 2025. Available online.

Triadafilopoulos, Triadafilos. 2022. Good and Lucky: Explaining Canada’s Successful Immigration Policies. In Policy Success in Canada: Cases, Lessons, Challenges, eds. Evert Lindquist, Michael Howlett, Grace Skogstad, Geneviève Tellier, and Paul t’ Hart. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Available online.

Vosko, Leah F. 2022. Temporary Labour Migration by Any Other Name: Differential Inclusion under Canada’s ‘New’ International Mobility Regime. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48 (1): 129-152.

Zhang, Tingting, Rupa Banerjee, and Aliya Amarshi. 2023. Does Canada’s Express Entry System Meet the Challenges of the Labor Market? Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 21 (1): 104-118. Available online.