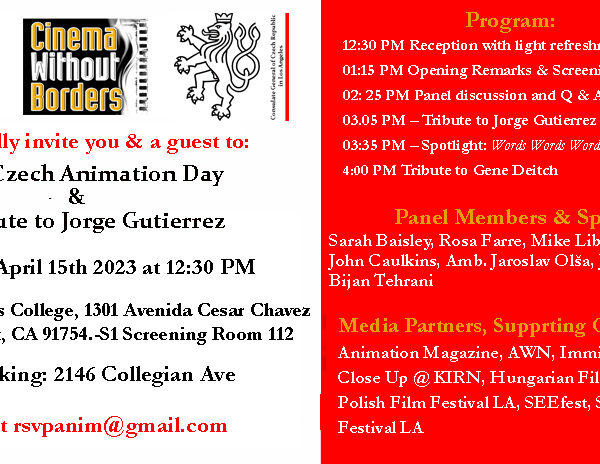

Photo: Article author Geoff Chin with his late father.

NAM/American Commercial News/New America Media, News Feature,

In Chinese

LOS ANGELES–My father was in a coma after his brain surgery due to some complications. The doctor wasn’t sure when he would awaken-if ever.

My siblings and I were caught off-guard. During one of the family meetings, we asked my mother, “if needed,” would we take away Dad’s life support and let him rest in peace. She couldn’t say a word while tears poured from her eyes.

The result of his surgery was not what we expected. My father didn’t leave behind a living will or advance healthcare directive stating his end-of-life wishes. We knew he was a strong person and would not give up on anything easily, but we didn’t know for sure what he wanted for his medical care or who would make medical decision on his behalf.

I wished he could at least wake up and tell me, even just for a simple direction.

Chinese American Compassionate Care

“A traditional Chinese would not discuss death or treatment and care before they get sick,” said Sandy Chen Stokes, RN, MSN, founder and board chair of the Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care (CACCC). This makes it difficult for family members when it comes to treatment, care and funeral arrangement for terminally ill patients, she said.

Stokes formed CACCC in 2005 to address the lack of linguistically and culturally appropriate end-of-life information and training available to the Chinese community.

Although palliative and hospice care are more common among the American public, Chinese Americans continue to have the lowest rates of hospice use of any group. Hence, the need for focused education and training for Chinese American patients and their family caregivers is especially great.

Since 2011, CACCC has conducted three training events for Chinese hospice and palliative care volunteers around California. Over 120 participants completed their training and provide services in their respective communities. These four-day, 30-hour trainings were supported by 17 hospitals and hospice care agencies that agreed to accept the CACCC volunteers on completion of their training.

The volunteers learn about such things as pain and symptom management, grief counseling and the differences between a person’s detailed advance health care directive stating his or her end-of-life wishes and POLST forms. Those are the shorter Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment document you and your doctor sign to tell medical staff what to do if you can’t communicate when the time comes.

The volunteers also learn the main difference between palliative and hospice care. Palliative care should begin soon after someone a very serious diagnosis and can include both curative and comfort care as needed. Hospice, though, only covers comfort care like pain control without medical treatment after doctors tell Medicare or other insurance the person has less than six months to live. (Medicare is changing this.)

The training goal is to prepare bilingual volunteers to provide linguistically and culturally sensitive care to Chinese American patients in hospice or palliative care settings.

According to Stokes, not every bilingual person is a qualified candidate for CACCC ‘s volunteer training. For instance, if someone just lost his or her loved one, the person will have to wait at least six months before being considered as a volunteer. They need time to heal and take care of their emotional needs.

Following their training, volunteers continue learning in community end-of-life care programs. In addition, CACCC has formed volunteer support groups to provide ongoing assistance to those trained volunteers.

Earlier this year, CACCC launched its “Heart to Heart Cards.” The poker-like cards are designed to facilitate communication about issues surrounding the end of life.

Volunteers use these cards to help people make state their wishes on their advance directives. Cards state, for instance, “I want someone to chant or pray after I die,” “I want my family to respect my wishes,” “If I’m going to die anyway, I don’t want to be kept alive by machines,” or simply, “I don’t want to suffer.”

Cultural and Language Barriers

“Maybe due to cultural and language barriers, most Chinese patients are more reluctant to talk about this issue,” said Fan Ming Hung, a clinical social worker at the Department of Support Care Medicine at City of Hope National Medical Center.

Patients often mistake palliative care as “giving up on treatment,” which Hung said is a big misconception. In palliative care, patients may be able to experience their last days in comfort without futilely invasive and often painful medical procedures. Research shows that most people at that stage want to spend their remaining time enjoying their family and loved ones.

Also at the City of Hope, Bonnie Freeman, RN, is one of the palliative care nurse practitioners who originally developed the widely used CARES Tool, a pocket guide initially developed for nurses as a quick reference for care of the dying.

In late 2013, Freeman and Hung helped create a team that also includes children’s specialists, a psychologist, a “patient navigator” and administrative staff members. They adapted the CARES Tool to include non-nursing and non-medical personnel better in their team support.

Hung noted, “Being part of this group helped me to feel more comfortable, not only in my clinical work with dying patients and grieving families, but with expressing and processing my feelings with colleagues and others.” He said the CARES guide has also helped him comfort and reassure family members, as they understood more about what to expect when a patient nears end-of-life.

He urged people not to be afraid when they hear the term “palliative care,” but to take advantage of the supportive services such care offers to help patients and families. He continued, “Therefore, do not hesitate to request assistance with your doctor or other member of the palliative care team with this difficult process.”

The Spiritual Dimension

A crucial aspect of every palliative care team is spiritual care.

According to Christina Shu, the lead interfaith chaplain at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC) in Los Angeles, “For Asian communities where social taboos keep many from taking ownership of their own body, people often leave medical decisions in the hands of their family. We want to educate people that you can make your own decision–and they should respect your wishes.”

Shu, who grew up in the Unitarian Universalist Church, said she always wanted to study different religions and interfaith dialogues. After earning a master’s degree from Harvard Divinity School, she joined CSMC’s spiritual care department in 2011.

One of 11 chaplains working with palliative care patients at CSMC’s Supportive Care Medicine program, Shu explained, “We are not here to tell people what religion or spiritual belief can do with their illnesses. Instead, we are having conversations that involve kindness, compassion and deep listening, leading patients to realize what gives them meaning and purpose of life, and hopefully that will give them strength to deal with the end-of-life issues.”

Her department often assists patients wishing to observe religion rituals and invites other clergy members to help, such as from Buddhist, Muslim or Hindu communities.

A common misunderstanding is that spirituality and religion are synonymous, Shu said. While religion is a belief system linked to rituals and practices, people may define spiritual support differently. For some, reading scriptures or chanting helps. For others, it may be spending time with family members, doing creative activities, or simply being outside in the sun.

Shu added, “We want people to leave behind a legacy. It is very important to tell your loved ones what you want, to start having a conversation.”

My family never got to have that conversation. My father did wake up from his coma, but only for two weeks before he passed away. We thought he was on his road to recovery at the nursing facility, and the palliative care option was never offered to us. Even though we were given the second chance, the question of what he would like for his medical care was never discussed. We thought we had more time and we could wait.

Geoff Chin wrote this article for the Chinese-language American Commercial News supported by New America Media’s Palliative Care Fellowship program, sponsored by the California Health Care Foundation.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Learning to Bring Comfort

“I missed two chances. Life is short and I don’t want to see that happening again,” stated Catherine Lan, who became a hospice and palliative care volunteer after feeling helpless when death visited two close friends.

A financial planner with nursing background, Lan is an avid volunteer in the Chinese community, mostly in health care programs. As a financial planner, she helps clients manage their wealth, including preparing their living wills. Death is one of the topics they talk about. However, she had a hard time dealing with two friends’ death.

“The first time was my best friend’s mother, and second time was a girl friend’s husband. While they were in their end-of-life stage, I wish I could do something, but at the same time I was afraid I would make things worse. Those were regretful and sorrowful experiences,” she recalled.

Lan joined the Buddhist Tzu Chi Foundation’s cancer-patients support group as a volunteer, hoping the religious and group power would strengthen her ability to support others. In 2011, she participated in the Chinese American Coalition for Compassionate Care’s volunteer training, gaining skill and confidence in handling issues of terminal illness.

Like many hospice volunteers, Lan said she needed a break. A few clients she had helped died recently, most in their 50s. “They were still young, it was too early for them to go,” she said. “I need some time to take care of my emotional needs.” As a Buddhist, she believes meditation and chanting help her release some stress.

In San Diego, at a center run by Chinese Christian Herald Crusades (CCHC), Grace Chu stressed, “Once we clear things up with all the myth and misunderstand, most people are willing to accept palliative and hospice care.”

Chu, who directs the CCHC center, was a hospice nurse and also currently runs a senior residential care facility in San Diego. She commented, “Just like teaching your students, you need to educate people in accordance with their aptitude and personality.” She often bring up the end-of-life care issue in a more relaxing and indirect way, while socializing with the seniors at her facility, or those she met at the CCHC center and Sunday school.

She believes, “When people know they leave their lives to God, it makes them less scared about death.” She has observed that religious people she has known have tended to die more peacefully than others.

–Geoff Chin