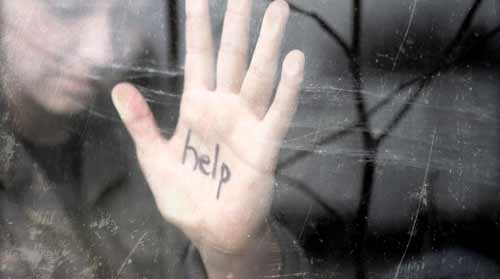

“After performing household duties throughout the day, we were subjected to sexual assault at night. Often, there would be more than one man who would rape and torture us. We have marks on our body,” one of them tells Firstpost.

She says the diplomat’s family knew about the abuse. Not only did they not try to stop it, they would beat the women as well. Armina Guru of Maiti Nepal India, an NGO which works on trafficking issues tells Firstpost that when the police raided the Gurgaon flat, “the women were being physically assaulted” and the medical examination confirms rape.

That all sounds pretty damning. But it probably won’t amount to a damn.

The Saudi Arabian mission has rejected the charges as false and unproven. There’s not even a pretence of conducting their own inquiry.

No matter what the charges, or how damning the evidence, the presumption of innocence is surely sacrosanct. But presumption of innocence means that someone should not be presumed to be guilty until a fair investigation or trial has been allowed to determine that charge. In this case however there will never be an investigation or trial. At most there will just be a flight home. It is not about the presumption of innocence as much as it is about the assumption of immunity.

For all the outrage, whether in India or Nepal, neither country will in the end do much to push the issue. Everybody needs the Vienna Convention more than they need justice for Nepali maids.

It was the same convention India invoked to demand all charges be dropped against its diplomat Devyani Khobragade accused of mistreating her children’s nanny. Though her strip search made her a cause célèbre, Khobragade was not alone.

India’s high commissioner to New Zealand and his wife were accused of ill-treating their cook who alleged he was assaulted and “kept in slavery”. He was simply recalled before it could balloon into a replay of the Khobragade case.

In 2009, the press counsellor at the Indian consulate in New York was accused of treating her domestic help like a “slave”. Two years later, the Indian consul-general in New York himself was accused of “inhuman treatment” of his maid. Both were quickly brought home.

A Saudi diplomat in London and his wife were accused of paying their Filipino and Indonesian maids less than minimum wage, no holiday pay and making them work up to 17 hours a day. A court admitted they were probably trafficking victims. But it offered them no relief saying it recognized the fact that it might seem “unfair” but that unfairness was “outweighed by the harm that would be caused by a failure to give effect to diplomatic immunity”. The diplomat did not even have to provide compensation.

Three Indian women who sued a Kuwaiti military attaché in the US did win special visas meant for trafficking victims but it does not mean the diplomat was prosecuted. One woman said when she made a mistake her head was shoved into a freezer with frozen chicken. “They were basically treated as slaves,” said the neighbour who helped them after one of them came knocking on his door.

Some of these stories might be true. Some might be concocted or exaggerated. But what gives pause is how often the word “slave” occurs in the charges. Slavery makes us think of dingy massage parlours, Dickensian carpet factories and sweatshops. Who would think a fancy suburban home could be the gleaming new face of modern day slavery? Slavery with all the mod cons. The tragic irony is the Vienna Convention which is meant to protect one class of people from abuse should itself be used by some as cover to abuse another class of people.

Sandip Roy is editor at Firstpost.com where this article originally appeared. He is the author of “Don’t Let Him Know.”