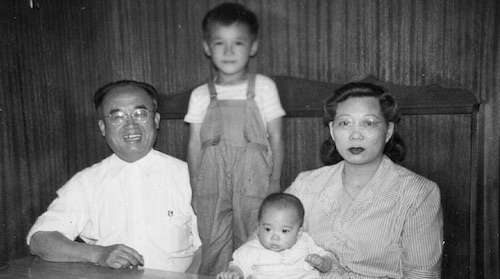

Pictured above: The author (standing) with his father, mother and niece in a booth at their Oakland Chinatown restaurant in the late 1940s. Photo courtesy of William Gee Wong collection.

My father came to America from China in 1912, the 30th year of the Chinese Exclusion Act, and somehow he was able to get in legally even though he, uh, didn’t tell the whole truth.

The three generations of Gees and Wongs that are his legacy are so grateful he was able to skirt the dreaded, racist Exclusion Act, and that he didn’t try to come here under the Trump Administration’s immigration proposal.

In his mid-teens, Pop, as I called him, was not well educated. He was not well off. He did not speak English. Those are the principal requirements of what the Trump administration wants our future immigration policy to have.

Another is having a job. Pop would have qualified, maybe. He had work waiting for him as a lowly paid herbalist apprentice in Oakland, California’s Chinatown.

Pop’s immigration story was hardly unique. He and thousands of other Chinese immigrants were able to get into America despite the exclusion law that spanned from 1882 to 1943.

Many used the infamous “paper son” scheme. This was making false birthright claims made possible, in part, by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and fire that destroyed official records. Without records, the government could not legally counter the birthright claims of immigrants like Pop, who said he was a “son of a native,” a category exempt from the exclusion law.

Pop and other Chinese immigrants wanted desperately to come here, largely to escape the utter political, economic, and social turmoil of China in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries – the fall of the Qing Dynasty, the republican revolution, civil wars, and in the 1930s, the Japanese invasion.

Here in America, because of yellow Jim Crow laws, they were forced to create parallel universes in the many Chinatowns in cities and towns, first in California and the west and eventually throughout America.

Ironically, those enclaves – ostracized, ignored, and targeted for violence as they sometimes were – nurtured self-reliance and survival skills that enabled Pop and his cohort to begin stable and useful lives for their descendants.

Their numbers were teeny. In 1880, just before Congress passed the exclusion law, Chinese were 0.0021 percent of the U.S. population. In 1940, just before its repeal, they were a barely measurable 0.0005 percent.

Supporters of the Trump immigration proposal deny its intent is racist against non-white people, but its effects, if ever enacted, could very well be. Why do the president and the Republican senators pushing this bill want to go backwards to a time when America was much whiter than it is today and going to be in the foreseeable future?

The Congressional debates over Chinese exclusion were blatantly and unapologetically racist. Example: Colorado Republican Senator Henry Teller in 1882 said, “The Caucasian race has the right, considering its superiority of intellectual force and mental vigor; to look down on every other branch of the human family…we are the superior race today. We are superior to the Chinese….”

Some of us descendants of so-called inferior races are worried that if President Trump gets his way on a new immigration policy as offered by Senators Tom Cotton and David Perdue, America will look to the world as returning to the bad old days when white supremacy was thought to be the norm.

Pop probably didn’t bother to think much about what American politicians believed. All he wanted was a better life for his growing family. He had three daughters born in China, and three more plus me born in Oakland.

One goal of the immigration bill is to decrease family reunification. A positive feature of the 1965 immigration reform was its family preference provisions that allowed immigrants to bring in members of his or her families. That feature has propelled the growth of immigrant families, especially from Latin America and Asia. Perhaps that is what repels Trump and his backward-looking supporters.

Pop worked hard to provide for his family in Oakland. He learned to speak, read, and write English at Lincoln School, where he graduated from the eighth grade as a 20-something. Besides his herbalist job, he peddled produce in a truck, ran grocery stores and restaurants, and worked as a welder at a Bay Area shipyard during World War II.

Oh, yeah: he ran an illegal business as well, in the 1930s. He sold lottery tickets in Chinatown when such a business was against the law. Many other Chinatown families did the same. After all, this was during the Great Depression, and local police and politicians took bribes to allow the trade to thrive into the 1950s.

To his last days in the summer of 1961, Pop felt he belonged in Chinatown but not in the wider white-dominated society. I, on the other hand, along with my sisters and our extended families feel we are as American as anyone else, regardless of racial or ethnic background.

Let’s hope that what the Trump-backed Cotton-Perdue proposal wants to do never happens, and that wiser and more humane lawmakers create immigration policies that make all of us feel as though we belong here in America.

William Gee Wong, author of Yellow Journalist: Dispatches from Asian America (Temple University Press, 2001) is writing a book about his father.